Shakespeare, Fleabag, and the Performance of Self

Reading up before a night at the theater

Claude

Richard II is one of Shakespeare’s most psychologically complex history plays — all poetry, no prose, which gives it this heightened, almost ritualistic quality throughout.

The basics: It’s about the deposition of King Richard II by his cousin Henry Bolingbroke (who becomes Henry IV). Richard is a weak, narcissistic ruler who’s squandered the kingdom’s resources and alienated the nobility. When he seizes Bolingbroke’s inheritance to fund a war in Ireland, Bolingbroke returns from exile, gathers support, and basically forces Richard to abdicate. The play tracks Richard’s fall from divine-right monarch to broken prisoner.

What makes it fascinating: Richard is a terrible king but a brilliant poet. As he loses power, his language becomes more beautiful and introspective — the play is really about watching someone transform from a symbol into a person. The central scene is the deposition, where Richard essentially performs his own downfall, shattering a mirror and delivering some of Shakespeare’s most gorgeous meditations on identity and kingship.

Key themes to watch for: The tension between the divine right of kings and political reality; the gap between performance and authenticity (Richard is always aware of his own theatricality); how language both creates and destroys power; and the question of whether deposing even a bad king breaks something fundamental in the social order.

The language is dense and formal but incredibly rewarding — Richard’s speeches about being “wasted” by grief, or comparing himself to Christ, or the gorgeous garden scene are all highlights. You’ll probably notice the play is structured almost like a long ritual of humiliation.

Enjoy! It’s a play that gets better the more attention you pay to its poetry.

Here’s the story arc so you can follow along:

Act I — The Setup

The play opens with a dispute: Henry Bolingbroke (Duke of Hereford) accuses Thomas Mowbray (Duke of Norfolk) of treason and embezzlement. They’re going to settle it with a trial by combat. But just as they’re about to fight, King Richard stops the duel and banishes them both — Mowbray for life, Bolingbroke for ten years (which Richard reduces to six).

Richard’s uncle, John of Gaunt (Bolingbroke’s father), is furious but dying. On his deathbed, Gaunt delivers a famous speech about England as “this sceptered isle” and warns Richard he’s destroying the kingdom. Richard dismisses him coldly. When Gaunt dies, Richard immediately seizes all his estates to fund a war in Ireland — which means Bolingbroke can’t inherit what’s rightfully his.

Act II — The Return

Richard goes off to Ireland. While he’s gone, Bolingbroke returns from exile (breaking his banishment) to reclaim his inheritance. Nobles start flocking to his side because Richard has been such a terrible king. Richard’s uncle York is left in charge and tries to be loyal to Richard, but he’s basically powerless.

When Richard returns from Ireland, he finds his support has collapsed. At first he’s confident — he believes in the divine right of kings, so God must protect him. But as the bad news piles up, he swings wildly between despair and defiance.

Act III — The Confrontation

Richard and Bolingbroke meet. Bolingbroke claims he only wants his inheritance back, but it’s clear he has all the power now. Richard is forced to submit. There’s a heartbreaking scene where Richard essentially performs his own humiliation, talking about how he’s being reduced from king to nothing.

The Queen has a brief, beautiful scene in a garden where gardeners compare the kingdom to an untended garden — a metaphor for Richard’s misrule.

Act IV — The Deposition

This is the centerpiece. Bolingbroke (now effectively in control) asks Richard to formally abdicate. Richard turns it into theater — he calls for a mirror, looks at his face, then shatters it, saying his grief has “destroyed” his face just as his kingship has been destroyed. He gives incredibly poetic speeches about identity and what it means to go from being a king to being nothing. Bolingbroke, now Henry IV, sends Richard to prison.

Act V — The Aftermath

Henry IV is now king, but he’s uneasy — deposing a king has consequences. There are small rebellions. Richard is in prison and delivers a long, gorgeous soliloquy comparing his prison cell to the world and trying to figure out who he even is anymore.

A loyal knight, Sir Piers Exton, thinking Henry wants Richard dead (based on an ambiguous comment), murders Richard in prison. Richard fights back and kills two assassins before dying.

Henry rejects Exton and the murder — he needed Richard dead but didn’t want the guilt — and vows to go on a pilgrimage to atone. The play ends with this unresolved guilt hanging over everything.

The through-line: Watch Richard transform from an arrogant, out-of-touch king to someone who becomes deeply human and self-aware through suffering. And watch how Bolingbroke goes from seeming justified to becoming morally compromised by taking the crown.

Oh, this is where the play really lives for a modern audience.

The narcissist’s collapse. Richard is a textbook narcissist — grandiose, thin-skinned, surrounded by flatters, convinced he’s special and untouchable. But unlike most dramatic villains, Shakespeare shows what happens when that bubble pops. Richard doesn’t just lose power, he has a full psychological disintegration. The “mirror scene” is devastating — he’s literally trying to see himself, figure out who he is without the role that defined him. Anyone who’s watched someone’s identity shatter when they lose status (a job, a relationship, social standing) will recognize this.

Grief as transformation. As Richard loses everything, he becomes more — more articulate, more self-aware, more human. There’s something deeply true about how suffering can crack people open. His prison soliloquy is him genuinely trying to think his way through who he is now. It’s like watching someone go through therapy in real-time, except it’s happening during a political catastrophe.

The gap between how we see ourselves and reality. Richard believes he’s God’s chosen one right up until he can’t anymore. The cognitive dissonance is painful to watch. We all have stories about ourselves that reality eventually contradicts — we’re the good guy, we’re competent, we’re loved, we matter. Richard’s tragedy is universal: what happens when your self-story collides with the truth?

Bolingbroke’s emotional flatness. This is subtle but brilliant — Bolingbroke barely has interiority in the play. He’s all action, strategy, political maneuvering. He doesn’t do the self-examination Richard does. Shakespeare seems to be asking: is this what effective leadership requires? A kind of emotional shutting-down? Bolingbroke wins but becomes hollowed out in the process.

The Queen’s helplessness. She loves Richard, sees him clearly (both his flaws and his humanity), and can do absolutely nothing. Her scenes are brief but gutting — the experience of loving someone who’s self-destructing while being completely powerless to stop it.

Performance vs. authenticity. Richard is always performing, always aware of his audience, always choosing his words for maximum dramatic effect — even in his most private moments. It raises this uncomfortable question: is there a “real self” underneath the performance, or are we just the roles we play? Very contemporary anxiety.

Humiliation and dignity. The deposition scene is Richard choreographing his own humiliation, trying to maintain some control over his degradation by narrating it beautifully. There’s something recognizable about trying to preserve dignity while everything falls apart — making your suffering mean something, turning pain into art or insight.

You’re watching someone who’s been completely insulated from reality finally crash into it, and Shakespeare doesn’t let him off easy — but he also doesn’t deny Richard’s humanity or the genuine transformation that suffering produces. It’s psychologically sophisticated in ways that feel utterly modern.

“Bolingbroke barely has interiority in the play. He’s all action, strategy, political maneuvering. He doesn’t do the self-examination Richard does.”

Is this because Shakespeare is portraying him as less self reflective? Or is he just a less developed character?

That’s the genius question, right? And honestly, I think it’s both — and the ambiguity might be the point.

The case for intentional characterization: Bolingbroke’s flatness feels deliberate because it’s such a stark contrast to Richard’s endless self-examination. Shakespeare gives Richard these massive introspective soliloquies where he’s constantly trying to understand himself, while Bolingbroke speaks in short, pragmatic bursts. He says what needs to be said to accomplish his goals, nothing more.

This creates a psychological portrait: Bolingbroke is someone who acts rather than reflects. He’s not interested in examining his motives or the moral weight of what he’s doing — he just moves forward. That kind of operational personality is real. Some people navigate the world through constant self-interrogation (Richard), others through decisive action without looking back (Bolingbroke). The play seems to suggest that political effectiveness might require not thinking too hard about what you’re doing.

The case for underdevelopment: Richard II is early in Shakespeare’s history cycle, and Bolingbroke becomes the protagonist of the next two plays (Henry IV Parts 1 & 2). It’s possible Shakespeare was still figuring him out, or deliberately saving his interiority for later. In Richard II, Bolingbroke is more function than character — he’s the force that brings Richard down, the political reality crashing into Richard’s poetry.

Why the ambiguity matters: Here’s what’s brilliant — we genuinely can’t tell if Bolingbroke is:

- Cynically manipulating everyone while hiding his true ambition

- Actually believes he only wants his inheritance back and gets swept up by circumstances

- Simply doesn’t examine his own motives and just does what feels necessary in the moment

Shakespeare never tells us. Bolingbroke never has a moment where he reveals his true intentions, even to himself. Is that because he’s shallow? Or because he’s opaque? Or because even he doesn’t know?

The play works either way. If Bolingbroke lacks self-reflection, it’s a commentary on how power attracts people who don’t agonize over their actions. If he’s just underdeveloped, it makes Richard’s psychological richness stand out even more — the falling king gets all the poetry and consciousness, while the rising king is almost a blank.

I lean toward intentional, because Shakespeare clearly could have given Bolingbroke soliloquies if he wanted to. The silence feels like a choice. But you’re right to wonder — it’s one of those things where you can’t completely separate authorial intent from theatrical effect.

What do you think as you watch it? Does his blankness feel like characterization or absence?

Perfect comparison - and I’d say Fortinbras is much more clearly just a structural element rather than a character. He’s barely in Hamlet, shows up mainly in reports, and exists to create contrast: while Hamlet agonizes over avenging his father, Fortinbras just acts - raises an army, marches on Poland, takes what he wants. He’s a plot device and a foil, not a psychological portrait.

Bolingbroke is different because he’s present throughout Richard II, driving the action, making choices, negotiating with other characters. We spend real time with him. Shakespeare could have made him a Fortinbras-style plot function - the external force that topples Richard - but instead Bolingbroke has actual scenes, relationships, ambiguous moments where you wonder what he’s thinking.

That’s what makes the blankness interesting. With Fortinbras, we don’t expect interiority because he’s architecturally a foil. With Bolingbroke, the absence of interiority becomes itself a kind of characterization - especially in contrast to Richard’s constant self-examination.

It’s like... Fortinbras is a sketch. Bolingbroke is a detailed portrait where the face is deliberately left opaque. You notice what’s missing because everything else is rendered so carefully.

The fact that Shakespeare then gives Bolingbroke (as Henry IV) rich interiority in the next plays suggests he was capable of it here but chose not to. Which makes me think the blankness in Richard II serves the play’s purposes - it makes Richard’s consciousness the entire emotional center while Bolingbroke remains this efficient, unreadable political force.

But yeah, you could argue I’m giving Shakespeare too much credit and he just hadn’t fully imagined the character yet. The line between “intentional artistic choice” and “limitation that happens to work” is always blurry with drama.

Great question — I’m trying to think of characters where the lack of self-reflection is clearly intentional characterization rather than just thin writing...

Tony Soprano has moments of this, interestingly. He goes to therapy but actively resists real insight — he’s allergic to self-examination even when it’s handed to him. The show makes his avoidance of reflection part of his pathology.

Don Draper in Mad Men — he’s constantly performing depth and brooding, but actually evades real self-knowledge. He reinvents himself but never actually examines why or what it costs. The show seems very conscious of this — his blankness is the point.

Patrick Bateman in American Psycho — pure surface, no interior life, just consumption and violence and status performance. Though that’s almost satirically extreme.

Characters in Hemingway often have this quality — they act, they do, they follow codes of behavior, but they don’t psychologize or examine their motivations. The lack of interiority is Hemingway’s whole aesthetic.

Ryan Gosling in Drive — deliberately opaque, almost affectless, acts on instinct and code rather than reflection. The blankness is stylized, intentional.

But here’s what’s tricky: most modern storytelling is so invested in interiority and psychological realism that characters who lack self-reflection often read as either villains, trauma victims, or failures of writing. We’ve inherited this post-Freudian assumption that self-awareness is good and its absence is pathological.

Bolingbroke is interesting because Shakespeare doesn’t moralize his lack of reflection — it’s just... how he operates. He’s effective because he doesn’t agonize. Modern storytelling would probably feel compelled to either condemn that or explain it with backstory.

Who else am I missing? This is harder than I thought.

Ha! Yeah, actually - Trump might be the most prominent real-world example of someone who operates with apparently zero self-reflection, and where that lack is clearly part of what defines him.

He doesn’t seem to have an inner life in any conventional sense - no visible self-doubt, no examination of motives, no wrestling with contradictions. He just... does things, says things, moves to the next thing. All action, all performance, no evident introspection.

And like Bolingbroke, it’s genuinely hard to tell: Is he cynically manipulating everyone? Does he actually believe his own mythology? Does he simply not think about it and just follows instinct? We can’t know because there’s no access point to interiority - no moment where he steps back and examines himself.

The parallel is even stronger because Trump’s effectiveness (at least with his base) seems connected to that lack of reflection. He doesn’t get paralyzed by doubt or moral complexity. He doesn’t agonize. He just acts decisively and moves forward, which reads as strength to people exhausted by overthinking.

Whereas someone like Obama was very Richardian - constantly examining, nuancing, seeing multiple sides, speaking in complex clauses that tried to hold contradictions together. Beautiful rhetoric, genuine thoughtfulness, but sometimes that introspection looked like weakness or indecision.

So yeah - Trump as Bolingbroke, seizing power through action and instinct while everyone else is still thinking about the implications. That... actually tracks uncomfortably well.

Though Trump never gets his Henry IV plays where the guilt catches up with him, unfortunately.

Obama as Richard in terms of the paralyzing effects of self-awareness.

Richard’s constant self-examination makes him a terrible king but a fascinating consciousness. He’s so absorbed in the poetry of his own experience, so aware of himself as a performer, so capable of seeing multiple perspectives (including his own failings) that he becomes unable to act decisively. His introspection is genuine and moving, but it’s also what makes him ineffective.

Obama similarly - that characteristic move of “on the one hand... but on the other hand,” the ability to see complexity and nuance, the self-awareness about his own limitations, the tendency to stand slightly outside himself and observe. Beautiful rhetorically, deeply thoughtful, but sometimes that very sophistication became paralysis. He’d give these complex, carefully hedged explanations while his opponents just acted.

Both have this quality of being almost too conscious, too aware of the performative nature of their role. Richard knows he’s performing kingship even as he does it. Obama always seemed aware he was performing “President” - you could see him thinking about how he was being perceived, calibrating, considering implications.

And both produce gorgeous language about their predicament while being in it. Richard’s prison soliloquy, Obama’s speeches about race or democracy - they’re articulating complexity in real-time, trying to think their way through impossible situations, making their struggle itself into art.

The tragedy is that this kind of consciousness - this ability to examine yourself, hold contradictions, see from multiple angles - might actually be incompatible with the ruthlessness that political power requires. Bolingbroke/Trump just take. Richard/Obama consider.

Shakespeare seems almost to be suggesting: maybe the people best equipped to think about power are least equipped to seize it.

Hamlet is the obvious Shakespeare predecessor — the prototype of paralytic self-reflection. But modern fictional Richards...

Jesse Pinkman in Breaking Bad — constantly examining his own guilt, articulating his moral horror at what he’s doing, aware of his own degradation in real-time. Compare him to Walter White, who’s pure Bolingbroke — action, rationalization, forward momentum with no real self-examination until it’s too late.

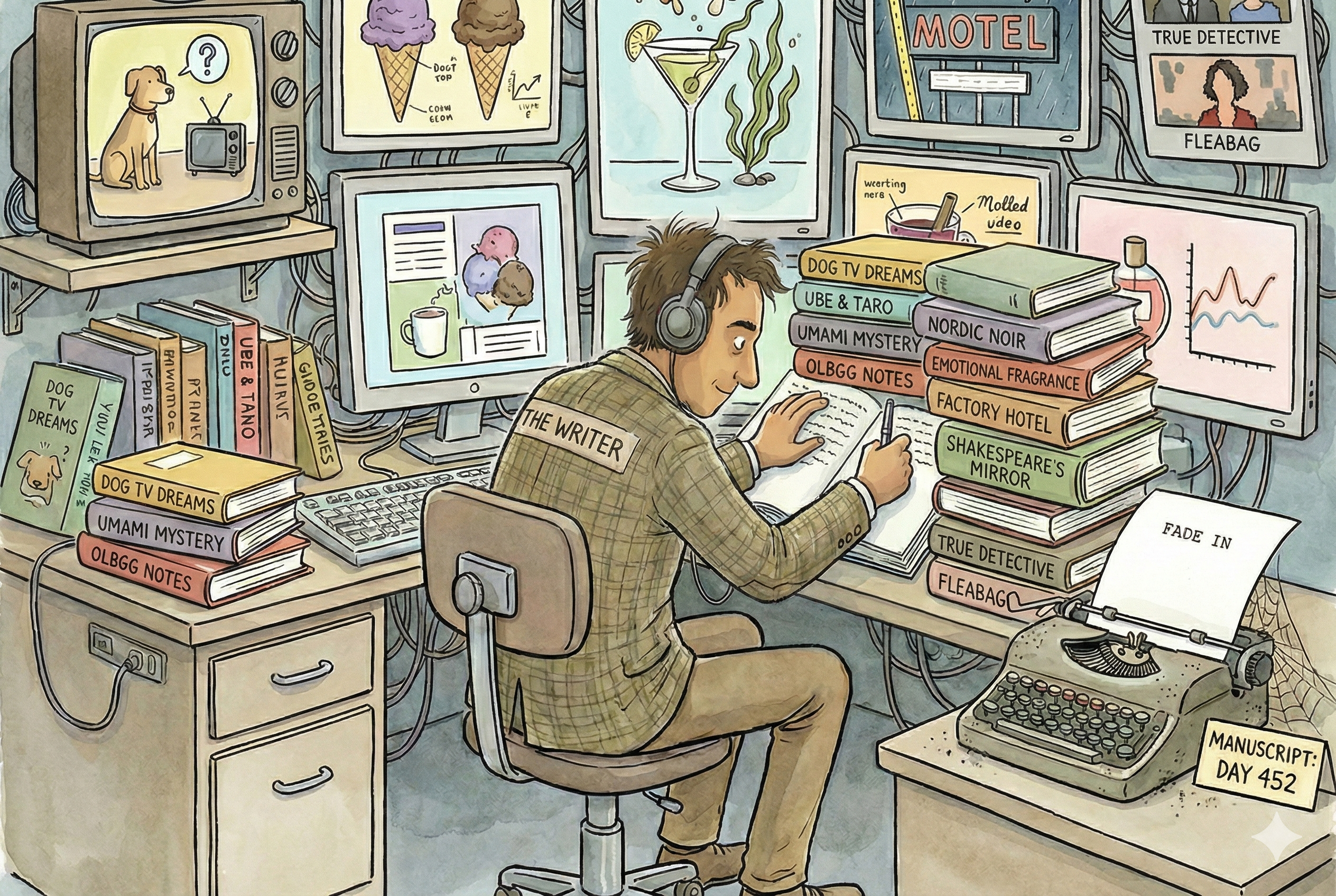

Rust Cohle in True Detective Season 1 — hyper-articulate about his own despair, constantly philosophizing about meaning and consciousness, turning his suffering into poetry. Though he’s more nihilistic than narcissistic.

Fleabag — she’s constantly breaking the fourth wall to examine herself, narrate her own failures, perform her pain for us while experiencing it. Very Richardian in that self-consciousness about performance.

BoJack Horseman — extremely Richard. Narcissistic, self-destructive, capable of devastating self-awareness but unable to translate that into change. He articulates his own awfulness beautifully but keeps doing awful things. The show is literally about whether self-examination without transformation means anything.

Kylo Ren maybe? Constantly torn, examining his own conflict, performatively tortured by his choices. Though he’s more adolescent than Richard’s sophistication.

Tyrion Lannister has shades of this — hyper-verbal, self-aware, turning his marginalization into wit and insight, though he’s more functional than Richard.

The Richard type in modern fiction tends to be the self-destructive intellectual who can articulate exactly why they’re failing but can’t stop failing. The character who turns their pain into language, who’s always performing their own consciousness for an audience (sometimes literally, like Fleabag).

What am I missing?

Rust Cohle:

THE parallel is in how both Richard and Rust turn existential crisis into performance. Rust has these long, gorgeous monologues about time being a flat circle, consciousness as a tragic misstep in evolution, the illusion of self — he’s constantly articulating a philosophical position about meaninglessness with almost religious intensity.

Like Richard, Rust is hyper-aware that he’s performing. He knows Marty (and we) are watching him philosophize, and there’s something almost narcissistic about how he polishes these ideas into aphorisms. He’s making art out of his despair, the same way Richard makes poetry out of his deposition.

But here’s the key difference: Rust’s introspection is about escaping the self — he wants to achieve some kind of transcendence through negation. Richard’s introspection is about desperately trying to find the self once his role as king is stripped away. Rust says “I think human consciousness was a tragic misstep in evolution.” Richard says “I live with bread like you, feel want, taste grief, need friends — subjected thus, how can you say to me I am a king?”

Both are trying to locate meaning through language when the structures that gave them identity have collapsed. But Rust ultimately remains opaque even to himself (he acts, investigates, moves forward despite the philosophy), while Richard becomes almost too transparent — we see every wound, every contradiction.

Fleabag:

This one’s even closer structurally. Fleabag is constantly breaking the fourth wall to narrate her own experience, examine her motives, perform her pain for us. She’s aware she’s being watched and turns that awareness into dark comedy and insight — exactly like Richard’s awareness that he’s performing his kingship, his suffering, his deposition.

The genius move in both is that the performance is real even though it’s performed. When Fleabag looks at the camera and tells us what she’s really thinking, it’s genuine — but it’s also curated, managed, presented for effect. When Richard shatters the mirror and says “I’ll read enough when I do see the very book indeed where all my sins are writ, and that is myself,” he’s genuinely wrestling with identity — but he’s also making sure his audience appreciates the metaphor.

Both characters use language and performance as survival mechanisms. Fleabag narrates herself to maintain control and connection (with us, since she can’t connect with people in her life). Richard narrates himself to maintain dignity when everything else is being stripped away.

And both have this quality where self-awareness doesn’t lead to change. Fleabag knows she’s self-destructive, keeps terrible men around, pushes away the people who care about her — she articulates all of this clearly — but keeps doing it anyway. Richard knows he’s been a terrible king, understands exactly how he got here, can describe his flaws with devastating precision — but that knowledge doesn’t save him.

The tragic irony: all that consciousness, all that self-examination, all that beautiful articulation of inner life... and neither can actually use it to avoid catastrophe. The performance of self-awareness becomes a substitute for actual transformation.

Though Fleabag eventually does change (the Hot Priest forces her to), whereas Richard just... shatters.

ChatGPT

Queer interpretations

Richard as a king for whom intimacy, aesthetics, and emotionalism are coded queerly (this has a long interpretive tradition).

There is a rich and very long interpretive tradition that reads Richard II through a queer lens — not in a reductive “Is Richard gay?” way, but in a deeper, more structural way about how he expresses power, intimacy, beauty, and emotion in ways that don’t conform to the play’s (or history’s) norms of masculinity.

And these interpretations go all the way back to the 19th century — long before queer theory had vocabulary for it.

Let me break down the main strands.

🌈 1. Richard’s “queer” kingship — a style of rule, not a sexual identity

Shakespeare presents Richard in stark contrast to:

- the martial masculinity of Bolingbroke

- the stoic, duty-first masculinity of York

- the brotherhood-of-arms masculine world of the nobles

Richard’s power is:

- aesthetic

- ceremonial

- inward

- poetic

- emotional

- theatrical

In the rigid gender logic of Shakespeare’s England, these traits read as:

- insufficiently “manly”

- feminized

- decadent

- suspicious

- “Other”

So queer readings don’t require assuming sexual desire — the style of his kingship is already in tension with the heteromasculine ideal.

This is why critics sometimes describe Richard’s rule as “queer sovereignty” — a mode of authority that operates through beauty, ritual, and emotion rather than violence, force, or rational calculation.

🌿 2. Richard is a character who expresses emotion in ways coded queerly

Richard:

- cries publicly

- speaks in lush, ornate language

- uses metaphors of beauty and fragility

- dramatizes his vulnerability

- leans toward performative self-fashioning

- collapses into melancholy instead of action

He expresses sorrow, grief, interiority, and even self-conscious theatricality with a fluency no other king in Shakespeare does.

This has made him deeply resonant for queer audiences who recognize:

- the performance of identity

- the heightened self-awareness

- the coded emotional life

- the sense of being out of step with dominant norms

💐 3. The favorites — Bushy, Bagot, Green — historically and dramatically read as queer-coded relationships

Shakespeare includes politically charged accusations that Richard:

- “favors” them

- elevates them unjustly

- neglects the nobles in favor of intimate, emotionally close male companions

Elizabethan audiences would identify this as a classic stereotype applied to kings seen as sexually or emotionally transgressive.

Historically, Richard II was accused of excessive closeness to male favorites. These accusations often weren’t literal sexual claims — they were political weapons, but they used the cultural shorthand of “queer intimacy.”

And Shakespeare leans into this.

Bushy, Bagot, and Green:

- are soft, courtly, aesthetic men

- exist in a homosocial intimacy around Richard

- are in tension with the masculine, militaristic nobles like Northumberland and Bolingbroke

This creates a symbolic queer court vs. straight warband dichotomy.

🌟 4. Richard’s poetic self-fashioning reads queerly

Richard doesn’t just speak beautifully — he performs himself as a work of art.

This links him to:

- Oscar Wilde

- the aesthetic movement

- the tradition of the queer dandy

- the “melancholy poet-king” archetype

Richard’s language is sensuous, lush, self-conscious, excessive — all qualities historically targeted as “unmanly” or queer-coded.

👁 5. His crisis of identity resembles queer self-interrogation

Richard’s existential breakdown asks:

- Who am I really?

- What is left when the role drops away?

- How do I live when the world no longer recognizes my identity?

These questions resonate strongly with queer and trans readings.

His language becomes about:

- masks

- performance

- authenticity

- the painful divide between inner self and outward role

This is rich territory for queer interpretations.

💔 6. The deposition scene as a queer emotional climax

When Richard holds up the mirror and studies his own face, many productions stage this as:

- a moment of queer self-recognition

- a confrontation with the socially unacceptable self

- a moment of being stripped bare

- a ritual of self-unmasking

It’s theatrical, vulnerable, intimate — nothing like Bolingbroke’s stoic, masculine political posture.

🎭 7. Productions often lean into this — sometimes very explicitly

Directors have staged Richard as:

- ethereal, androgynous

- effeminate by the standards of his peers

- delicate and emotionally expressive

- a gay or queer-coded man navigating a hostile masculinist world

Some modern productions cast Richard with:

- queer-identifying actors

- androgynous performers

- non-binary or gender-nonconforming costuming

- choreography that emphasizes his difference

This makes the play vibrate with contemporary resonance.

❤️ 8. Why queer audiences attach to Richard

Because Richard’s tragedy feels deeply relatable:

He performs himself beautifully. He knows he’s being watched. He uses language to survive. He expresses vulnerability others find suspect. His emotional life is too large for the role he’s expected to play.

His downfall isn’t just political. It’s the tragedy of a person who doesn’t fit the world his culture demands.

⭐ Bottom line

Queer interpretations of Richard II aren’t about reading him as “secretly gay” but about understanding the play as a powerful exploration of:

- non-normative masculinity

- emotional expressiveness

- performance as identity

- intimacy between men

- aestheticized power

- the cost of being different in a rigidly gendered world

It’s a play that becomes astonishingly modern when viewed this way.

If you want, I can walk you through:

- how different productions staged Richard’s queerness

- queer coded moments in the text

- how Bolingbroke’s masculinity functions as the opposite

- how this reading interacts with the political themes