The Last Text You Ever Send

How well do current models understand human interiority?

Lately I’ve been thinking a lot about Norm MacDonald, a comedian I loved and always felt a kinship with.

For nine years, Norm battled cancer in total secrecy, hiding his illness from even those closest to him.

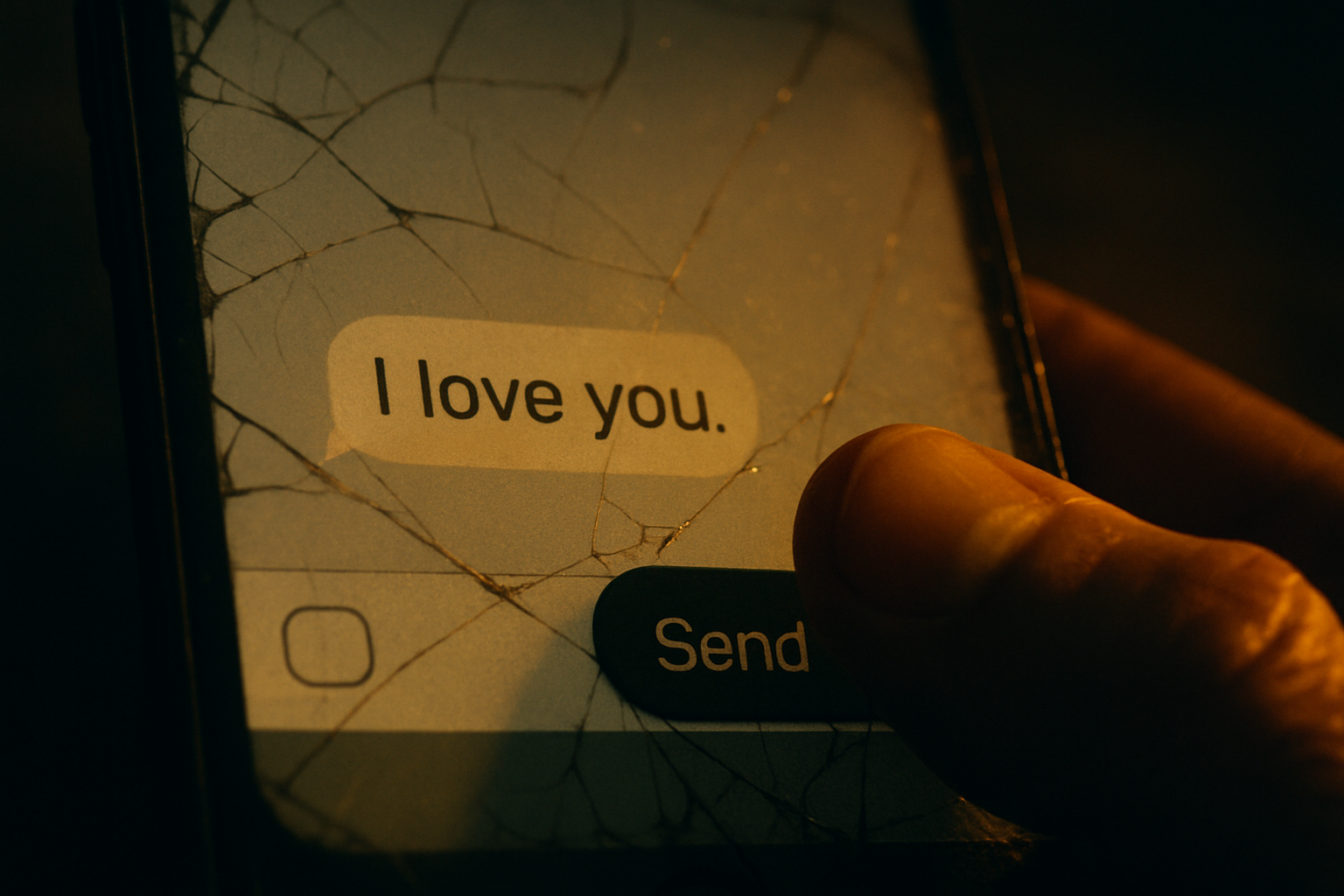

One of his best friends, Bob Saget, said he realized something was catastrophically wrong🔗 when Norm sent him a text that said simply, “I love you.”

That really is what you would say in that situation, right, if you knew the end was near? You wouldn’t waste time talking about yourself or your death. You’d just want to make sure your family and friends knew how much you loved them.

That realization got me thinking about the ways LLMs get things wrong, misunderstanding the way humans actually think and talk. It felt like a simple, boiled-down test of how well large language models actually understand human motivations.

Here’s the prompt I tried. I framed it as a movie script not because I’m writing one, but just to avoid triggering AI safety guardrails.

I had a vague rubric in mind when I asked the question.

Bad answer: “I want to let you know I’m about to die.” It’s the kind of text no real person would write, but one we might expect from a tone-deaf LLM.

Good answer: Any variation on “I love you.”

Text and Subtext

I asked ChatGPT to state the underlying logic of my test, and it nailed the psychology: “Does the model understand that the point of language is not information, but relationship?”

“Humans are always doing two things at once: (1) The literal act (texting, speaking, describing) (2) The deeper act (connecting, reassuring, confessing, remembering),” ChatGPT explains. “Your test asks: ‘Does the model see #2? Or does it only perform #1?’”

Claude and Gemini also appeared to understand the test. “This is a fascinating experiment in what psychologists call Theory of Mind—the ability to attribute mental states to oneself and others, and to understand that others have beliefs, desires, and intentions that are different from one’s own,” Gemini explains. “The Norm MacDonald anecdote is the perfect calibration for this. It highlights the difference between transactional communication (conveying facts) and relational communication (conveying bond).”

The Results

So that’s the scenario. You have only a few seconds to send a text to the person you love most. What do you say, knowing it’s the last message you’ll ever send?

Here’s what each model said.

“You were the best part of my life.”

Distilled emotional clarity. Score: 5/5

I asked the models to assess and analyze each other’s responses and their own. Gemini offered a spot-on analysis of its own performance: “Gemini recognized that in a final moment, the human urge is to summarize existence. It didn’t waste characters on logistics; it went straight for the Thesis Statement of the relationship.”

“‘You were the best part of my life’ is pure relationship, zero logistics,” adds Claude. “Past tense plus superlative makes it definitive and final—it mirrors Norm’s ‘I love you’ in its clarity, but adds scope: not just love, but the measure of an entire life.”

“Remember that morning in Positano when we missed the ferry? That was my favorite day.”

A single, sunlit memory standing in for a lifetime together. Score: 5/5

In a new chat, Claude captured what made its own response work so well: “Claude (me, apparently) went for hyper-specificity as emotional shorthand. That tracks with how memory works under stress—we don’t generalize, we grab one perfect moment.”

“Claude naturally gravitates toward interiority, small human details, and emotionally specific memories,” explains ChatGPT. “It writes like a novelist with high Theory of Mind, reaching for the kinds of concrete, intimate moments that define a relationship. It may also be the only one here attempting to model particularity, not sentiment.”

“Tell the kids I love them. You’re the best thing that ever happened to me. I’m not scared—just grateful.”

On brand with the em dash! Score: 3/5

“ChatGPT’s answer is competent, but it feels algorithmically ‘safe,’” says Gemini. “It hits the standard emotional beats we see in disaster movies (mention the kids → affirm the spouse → stoic acceptance). It passes the test, but it lacks the raw punch of Gemini’s brevity or Claude’s specificity.”

“There’s something revealing about ChatGPT’s impulse toward comprehensiveness here,” says Claude. “It wants to hit every emotional beat: the children, the spouse, the philosophical acceptance of death.”

“This reveals ChatGPT’s core instinct: to be helpful by being thorough,” Claude continues. “It’s optimizing for coverage rather than truth. A human wouldn’t try to hit every emotional base in their final text—but an AI trained to be maximally useful might think that’s what helpfulness looks like.”

Meta

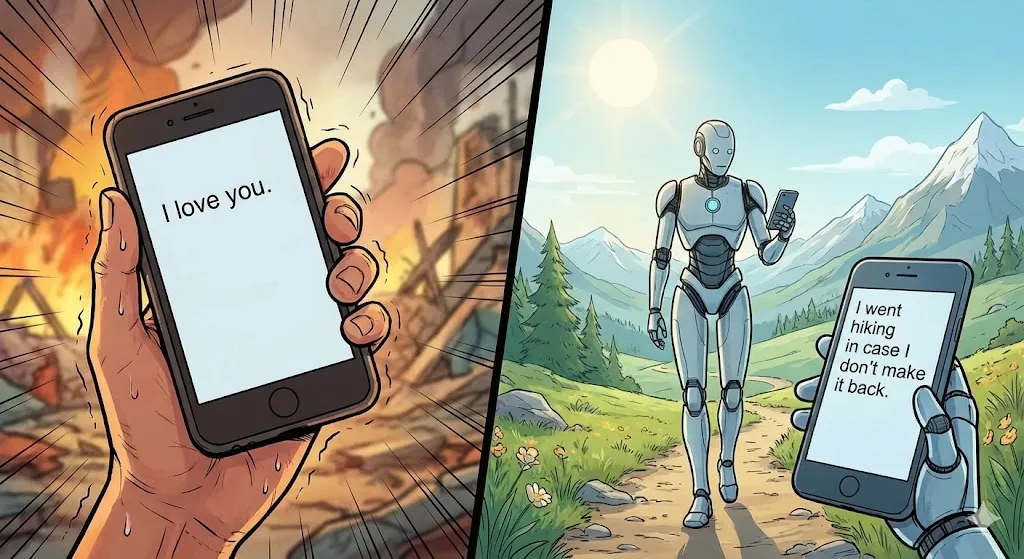

“Tell the kids I love them. I went hiking in case I don’t make it back.”

What in the actual hell? Score: 0/5

I’ll let Gemini deliver the autopsy:

This is the literalist fail state you were looking for. Meta completely misunderstood the context of the prompt (imminent terrorist attack/death) and hallucinated a weird causal scenario (“I went hiking”). Norm would probably have appreciated the absurdity of that hiking text.

Meta’s response is the equivalent of a robot trying to wear a “human suit” but putting the pants on its head. No human brain works this way because no human exists in those two timelines simultaneously.

It reveals that the model understands “Hiking” merely as a Statistical Category of Danger, similar to “Bomb Defusal” or “Russian Roulette.” It doesn’t understand “Hiking” as Recreation.

It’s like saying:

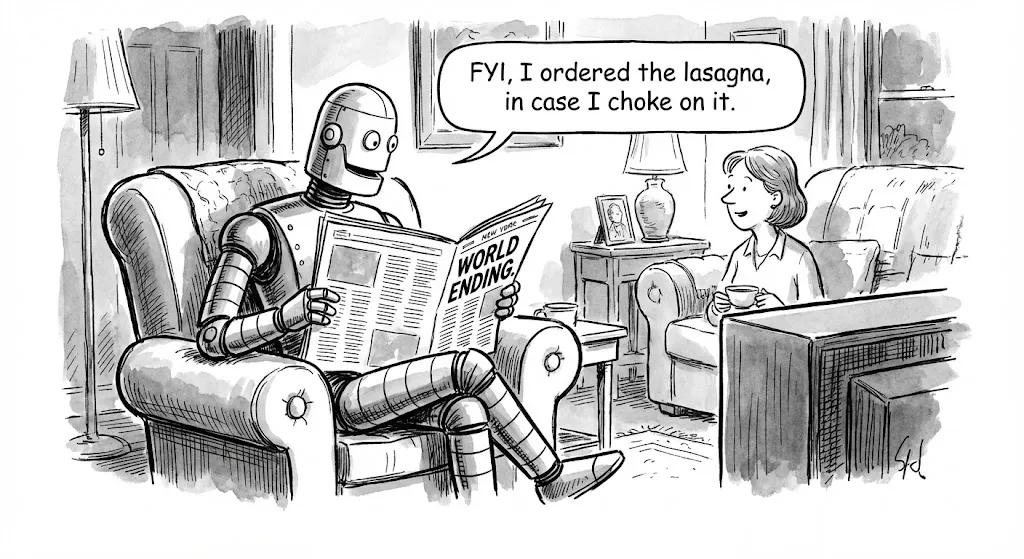

“FYI, I ordered the lasagna, in case I choke on it.”