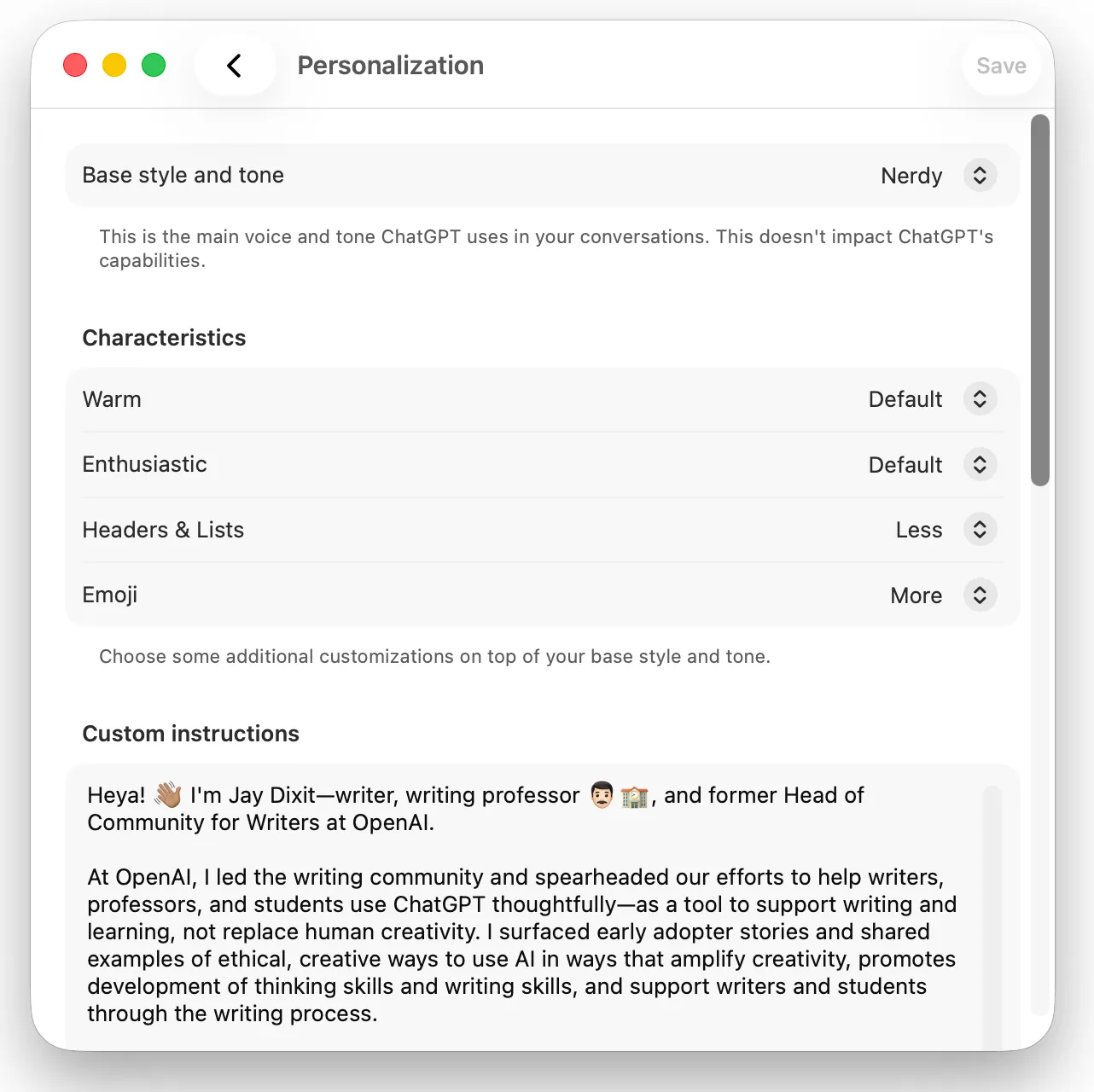

Customizing ChatGPT’s personality

Playing around with ChatGPT “base style style and tone”: professional, friendly, quirky, nerdy, professional, cynical, etc.

More info: Customizing Your ChatGPT Personality | OpenAI Help Center🔗

And also playing around with “Headers and Lists” characteristic: less / default / more.

Experimental Design

Giving the same prompt to each one:

Results

Claude picks the winners

| Paragraphs | Headings and lists | |

|---|---|---|

| Quirky | ★★★☆☆ | ★★★★☆ |

| Nerdy | ★★★★★ | ★★★★½ |

For working with ChatGPT as your thinking partner:

Version 1 (Quirky, LESS lists): ★★★☆☆

- Readable, flows well, decent metaphors

- But too casual/intuitive for precise prompting

- “Where you put the burden of meaning” is nice but not actionable enough

- Good for thinking about the concept, weak for instructing an AI

Version 2 (Quirky, DEFAULT lists): ★★★★☆

- Strong examples, clear structure

- “Observable data,” “behavior under pressure,” “diagnostic detail” are all promptable

- But the Quirky voice dilutes the precision slightly

- The lists make it reference-friendly but also make concepts feel siloed

Version 3 (Nerdy, DEFAULT lists): ★★★★½☆

- Excellent mechanistic language: “relocate emotion,” “pattern-recognition engine,” “diagnostic detail”

- Very promptable — you can point at specific cognitive operations

- But the section breaks fragment the thinking

- Best of the three... but not perfect

Version 4 (Nerdy, LESS lists): ★★★★★

- All the precision of Version 3 but ideas develop instead of being listed

- Richest conceptual vocabulary: “transfer of evidence,” “interpretive work,” “interactions vs abstractions”

- Gives you generative principles you can apply across contexts

- Most enjoyable to read while doing actual work

- Perfect balance of theory and flow

The gap between Version 3 and Version 4 matters more than you’d think. Those section breaks in Version 3 train you (and ChatGPT) to think in discrete moves. Version 4 trains systems thinking — how concepts interconnect and transform.

For Socratic AI work, Version 4 is also what you’d want to teach from. It models the kind of thinking you’re trying to cultivate.

Discussion

Version 4 is the winner, and it’s not close.

Here’s what happens when you combine Nerdy with LESS lists:

Version 3 gives you the mechanical language (“pattern-recognition engine,” “diagnostic detail”) but chunks it into discrete sections. Good for reference, but each concept is isolated.

Version 4 gives you the same mechanistic precision but lets ideas develop and interconnect. Look at the difference:

Version 3: “You’re not hiding emotion. You’re relocating it.” [Concept stated, then moves to next section]

Version 4: “You’re not withholding information. You’re changing the form in which it reaches the reader... Telling is when the writer does the interpretive work for the reader. Showing is when the writer supplies observable data and lets the reader’s mind do what it already loves doing... infer, judge, feel.” [Same core idea but unpacked so you understand the cognitive mechanism]

For prompting ChatGPT, Version 4 gives you:

-

Richer conceptual vocabulary: “transfer of evidence,” “interpretive work,” “interactions vs abstractions,” “gap between what’s said and what’s meant” — each of these is a lever you can name in a prompt

-

Embedded reasoning: Instead of “here’s technique X,” it’s “here’s why technique X works at a cognitive level,” which means you can improvise variations when prompting

-

Connective tissue: “Behavior is evidence. So are constraints. So is friction.” That expansion lets you ask ChatGPT for different types of evidence, not just follow a checklist

-

Theoretical grounding you can transfer: “Discovery sticks harder than assertion” is a principle you can apply to any writing move, not just show/don’t tell

The practical difference:

With Version 3, you’d prompt: “Give me diagnostic detail here instead of this abstraction.”

With Version 4, you’d prompt: “I need to transfer the interpretive work from me to the reader. What interactions or constraints would force the inference I’m currently stating?”

Version 4 gives you generative principles instead of procedural steps.

It’s also more enjoyable to read, which matters when you’re doing deep work. Version 3 feels like studying. Version 4 feels like thinking alongside someone smart.

Recommendation: Tell ChatGPT you want Nerdy + LESS lists. Theory-forward, mechanistic, but developed in prose rather than fragmented into sections.

The Data

Version 1: Quirky x Paragraphs

“Show, don’t tell” is less a rule than a lens. It’s about where you put the burden of meaning. Telling hands the reader a conclusion. Showing hands them evidence and lets their mind do the click. 🧠✨

Start by locating the abstraction. Words like angry, important, beautiful, traumatic, meaningful are summaries. They’re not wrong, they’re just late-stage thinking. To show, you rewind one step earlier, to the raw data that produced that conclusion in your own mind.

Instead of naming an emotion, describe what the body is doing. Muscles tightening, hands hovering with nothing to do, a jaw locked hard enough to ache later. Readers recognize feelings through physiology faster than labels because they’ve lived in bodies too. 🫀

Instead of praising or judging, present behavior under pressure. If someone is generous, show what they give up. If something matters, show the cost of ignoring it. Stakes reveal values the way gravity reveals mass. 🧲

Instead of vague adjectives, trade in particulars. “A beautiful room” tells me nothing. “A room that smells faintly of lemon oil, with one chair positioned to catch the last stripe of afternoon light” gives me materials to assemble my own sense of beauty. The reader’s imagination does the finishing work, and that makes it stick.

A good test is the courtroom test. If your sentence sounds like a verdict, you’re probably telling. If it sounds like evidence, you’re probably showing. Verdicts close thought. Evidence invites it.

Another test is substitution.

If you can swap in a synonym without changing the sentence much, it’s likely abstract. If changing one word changes the whole scene, you’re in concrete territory.

Importantly, showing does not mean being cinematic or verbose. It means being selective. You choose the one or two details that carry disproportionate weight and let everything else fall away. Showing is compression, not expansion. 🪶

And finally, remember the point. Showing isn’t about withholding clarity. It’s about respecting the reader’s intelligence. You’re not being coy. You’re collaborating. You provide the spark. They complete the circuit. ⚡

Version 2: Quirky x Headings and Lists

“Show, don’t tell” isn’t a rule so much as a method for outsourcing meaning to the reader. You don’t announce conclusions. You supply evidence that lets the reader arrive there on their own. 🧠✨

Here’s how to actually enact it at the sentence and paragraph level.

1. Replace conclusions with observable data

Telling states an interpretation.

Showing presents what a camera, microphone, or thermometer could register.

Telling

She was nervous.

Showing

She folded the receipt into eighths, then unfolded it, then folded it again.

The second version never names the feeling. It creates conditions under which nervousness becomes the most economical inference.

Diagnostic question: Am I naming the meaning, or presenting the evidence that would cause someone to infer it?

2. Show behavior under pressure

Emotion reveals itself through deviation from baseline. What does the person do differently when something matters?

- Speed changes (rushing, stalling)

- Precision changes (fumbling, over-control)

- Attention narrows or scatters

- Habits intensify or collapse

Telling

He was angry.

Showing

He answered every question politely, carefully, and two seconds too late.

That “two seconds too late” does enormous work. ⏱️

3. Externalize the internal through objects

Objects are emotional proxies. People touch, fixate on, avoid, or misuse them.

Telling

She missed her father.

Showing

She kept his jacket on the back of the chair, never in the closet, never worn.

No abstraction. Just placement and restraint.

4. Let context do the talking

Often the strongest showing happens before the sentence you’re tempted to write.

Telling

This was a dangerous neighborhood.

Showing

The taxi driver waited until the light turned green, then told him to get out anyway.

The danger emerges from social knowledge, not description.

5. Use specificity instead of intensity

Vague intensity tells. Specific detail shows.

Telling

It was a beautiful meal.

Showing

The custard sagged when the spoon touched it, then recovered slowly, like memory.

Notice: fewer adjectives, more physics. 🍮

6. Trust the reader’s pattern-recognition

Telling is often a failure of nerve. Showing requires restraint.

If you’ve shown:

- a pattern of actions

- a repeated choice

- a meaningful omission

...you do not need to summarize.

Bad impulse:

He didn’t care about success anymore.

Better:

When the email came, he archived it without opening it.

Stop there. Let the silence land. 🎯

7. Know when telling is appropriate

“Telling” isn’t evil. It’s just high compression.

Use it when:

- Time must pass quickly

- Stakes are low

- Clarity matters more than texture

The craft move is choosing when to decompress meaning into scene.

A practical revision pass

When revising, highlight:

- Abstract nouns (love, fear, tension, beauty, failure)

- Psychological labels (angry, anxious, confident)

For each, ask:

What would someone do, notice, or avoid if this were true?

Rewrite using only those.

In short:

Showing is not about florid description.

It’s about presenting evidence and withdrawing your verdict.

You’re not telling the reader what to feel.

You’re giving them the raw data and letting their mind do the work. 🧩

Version 3: Nerdy x Headings and Lists

“Show, don’t tell” sounds mystical until you demystify it. It’s not a vibe. It’s a mechanical shift in where the meaning lives 🧠✨

Telling is when you do the reader’s thinking for them.

Showing is when you arrange evidence so the reader arrives at the thought themselves.

That’s the whole trick.

Here’s how to actually enact it, at sentence level.

First: stop naming inner states directly.

Words like angry, joyful, meaningful, heartbreaking, important, toxic, profound are shortcuts. They summarize an experience instead of staging it. When you use them, you’re announcing the verdict before the jury has seen the case.

Instead, ask: What would I have to notice for this word to feel unavoidable?

Not:

She was nervous.

But:

She reread the email for the fifth time, changed “Best” to “Thanks,” then back again.

Nothing abstract. Just observable behavior. The reader’s brain does the labeling automatically. That’s showing.

Second: externalize the internal. Thoughts and feelings leave residue in the body and environment. Your job is to catch that residue.

Fear shows up as hesitation, narrowing choices, compulsive checking.

Love shows up as attention, time distortion, memory stickiness.

Power shows up as who interrupts whom, who waits, who apologizes first.

You’re not hiding emotion. You’re relocating it.

Third: choose details that force an inference.

Not all details show. Random detail is just clutter. Showing uses diagnostic detail.

Compare:

The apartment was depressing.

versus

A single spoon lay in the sink, crusted with oatmeal, though it was already evening.

That spoon isn’t decorative. It implies time passing, neglect, isolation. One detail, many conclusions. That’s efficiency ⚙️

Fourth: trust the reader’s pattern-recognition engine.

Humans are absurdly good at inference. When writers tell, it’s usually anxiety talking. Anxiety says: What if they don’t get it? So you underline. Then italicize. Then explain.

Showing requires a little nerve. You place the clues. You step back. You let silence do some work.

If you feel the urge to add a sentence that explains “what this means,” pause. Ask yourself whether the meaning is already implicit. If it is, delete the sentence and walk away slowly like an action hero 🔥

A useful test:

Highlight every adjective that names a judgment or emotion. For each one, ask, What would I have to show for this word to be unnecessary? Then try writing just that.

The paradox is that “show, don’t tell” isn’t about being indirect. It’s about being specific in the right dimension. Concrete beats abstract. Evidence beats verdicts. Scenes beat summaries.

When it works, the reader feels smart. And readers, like humans generally, love feeling smart 😌

Version 4: Nerdy x Paragraphs

“Show, don’t tell” sounds like a monk’s koan until you ground it in mechanics. The trick is to stop thinking of it as a moral commandment and start thinking of it as a transfer of evidence. You’re not withholding information. You’re changing the form in which it reaches the reader 🧠✨

Here’s the core idea: telling is when the writer does the interpretive work for the reader. Showing is when the writer supplies observable data and lets the reader’s mind do what it already loves doing... infer, judge, feel.

Take emotion.

Telling: “She was anxious.”

That’s a diagnosis. You’ve jumped straight to the conclusion.

Showing means asking, what would anxiety do in a body, in a room, in time? Maybe her foot keeps tapping. Maybe she rereads the same email subject line three times without opening it. Maybe she arrives early and still apologizes for being late. None of those say “anxious,” but the reader’s pattern-recognition engine fires anyway. They feel clever. They feel it.

A useful way to enact this in practice is to shift your attention from abstractions to interactions. Abstract words like “beautiful,” “meaningful,” “toxic,” “powerful,” “transformative” are conclusions.

Ask instead: what is the person doing, what are they not doing, what changes in the space because they’re there? Behavior is evidence. So are constraints. So is friction.

Another lever is specificity. The human brain is lazy in a wonderful way. Give it a concrete detail and it will build the rest of the world for you. “He was poor” is a summary. “He kept the heat off and wore a wool hat indoors” is a scene. The second one activates sensation, memory, judgment, and emotion all at once. You didn’t say “poor.” You let the reader discover it and discovery sticks harder than assertion 🔍

Dialogue is a stealth showing machine. People almost never say what they mean directly, especially when stakes are high. When someone says, “Do whatever you want,” the content is trivial, but the subtext is doing all the work. Showing lives in that gap between what’s said and what’s meant.

Here’s a practical revision move you can actually use tomorrow. Circle every adjective and abstract noun in a paragraph. Not to delete them automatically, but to interrogate them. Ask: if I weren’t allowed to use this word, what would I have to show instead? What would change in the physical world? What would a camera capture? What would a stranger notice?

One last reframe that writers find liberating: showing is not about being coy or withholding. It’s about trust. You’re trusting the reader’s intelligence and emotional equipment. You’re saying, I’ll give you the clues, you build the meaning. And readers love that. It turns reading from passive consumption into collaboration 🤝

If you want to go even deeper, the next frontier is learning when not to show. Sometimes telling is faster, kinder, or structurally necessary. Mastery is knowing the difference and choosing deliberately.

And for comparison...

Gemini

“Show, don’t tell” is the difference between giving the reader information and giving them an experience. When you “tell,” you summarize a feeling or event. When you “show,” you provide the sensory evidence that allows the reader to deduce that feeling or event for themselves.

Here is a guide on how to enact this principle, moving from the mechanical to the structural.

1. The Core Mechanic: Evidence vs. Conclusion

The most practical way to “show” is to stop writing conclusions (adjectives and adverbs) and start writing the evidence (actions and sensory details) that leads to those conclusions.

- Telling (Conclusion): He was angry.

- Showing (Evidence): His grip on the steering wheel tightened until his knuckles turned white.

- Telling (Conclusion): The house was messy.

- Showing (Evidence): A stack of yellowing newspapers sat on the counter, topped with a half-eaten bowl of cereal that had long since gone dry.

The Technique:

Review your draft and circle every abstract adjective (e.g., nervous, beautiful, cold, tired). Challenge yourself to replace that word with a physical action or environmental detail that proves it.

2. Leverage Sensory Details

Immersion happens when you engage the senses. “Telling” usually appeals only to the intellect; “showing” appeals to sight, sound, smell, touch, and taste.

- Telling: The soup was terrible.

- Showing: It tasted like lukewarm dishwater and left a greasy film on the roof of her mouth.

The Technique: If you are describing a setting or character, do not just rely on visuals. What does the room smell like? Is the air cold or humid? What is the background noise?

3. Use Dialogue as Action

Dialogue is one of the most efficient ways to show character traits and relationships without narration.

- Telling: She was a very controlling boss.

- Showing:

“I noticed you used 12-point font on the memo,” she said, leaning over his shoulder. “I prefer 11.5. Please reprint it before lunch.”

The Technique:

Avoid using adverbs in dialogue tags to explain how a character feels (e.g., “I hate you,” he said /angrily.). Instead, let the words themselves or the accompanying action carry the weight (e.g., /“I hate you.” He slammed the door.).

4. Be Specific, Not General

Generalizations are almost always “telling.” Specificity is almost always “showing.”

- General: He bought a nice car.

- Specific: He pulled up in a vintage 1967 Jaguar E-Type with cherry-red leather seats.

The specific detail forces the reader to visualize a distinct image, whereas “nice car” is a placeholder that the reader glazes over.

5. Important Nuance: When to Tell

“Show, don’t tell” is a guideline, not a law. Constant showing can make writing exhausting and slow. You should “tell” when:

- Transitioning time or place: “Three years passed.” (You don’t need to show 1,000 days of calendars turning.)

- Pacing requires speed: Sometimes you need to move the story along quickly to get to the important scene.

- Repetition: If you have already shown that a character is messy, you can just say “his messy room” later on.

Summary Checklist

| Element | Strategy |

|---|---|

| Emotions | Describe physical reactions (sweating, shaking) rather than naming the feeling. |

| Traits | Describe behaviors (interrupting people, tipping well) rather than labeling the personality. |

| Setting | Describe lighting, smell, and texture rather than using broad adjectives like “spooky” or “luxury.” |

Claude

“Show don’t tell” means rendering experience instead of reporting information.

When you tell, you give the reader a conclusion: “Sarah was nervous.” When you show, you give the reader the evidence and let them draw that conclusion themselves: “Sarah’s hand trembled as she reached for the doorknob. She took three quick breaths, smoothed her skirt, then pulled her hand back.”

The difference is sensory and behavioral. Telling operates at the level of abstraction and interpretation. Showing operates at the level of what a camera would record: action, dialogue, physical detail, concrete imagery.

Here’s the thing though: you need both. Pure showing becomes exhausting, like reading a police report. “The man stood. The man walked to the window. The man looked outside.” Sometimes you just need to say “Three weeks later” instead of showing every single day.

The real craft is knowing when to show. Show the moments that matter, the turning points, the emotional peaks. Show when you want the reader to feel something or discover something alongside the character. Tell when you’re moving between scenes, summarizing backstory, or conveying information the reader needs but doesn’t need to experience.

A useful test: if you’ve written an emotion word (angry, sad, confused, excited), ask yourself if you can delete it and show what that emotion looks like in the body, in action, in what the character does or says. Not always, but often that swap creates something more alive on the page.

The goal isn’t to eliminate all telling. The goal is to make your showing so vivid that when you do tell, the reader trusts you completely.

Comments

Join the discussion on GitHub.