ChatGPT

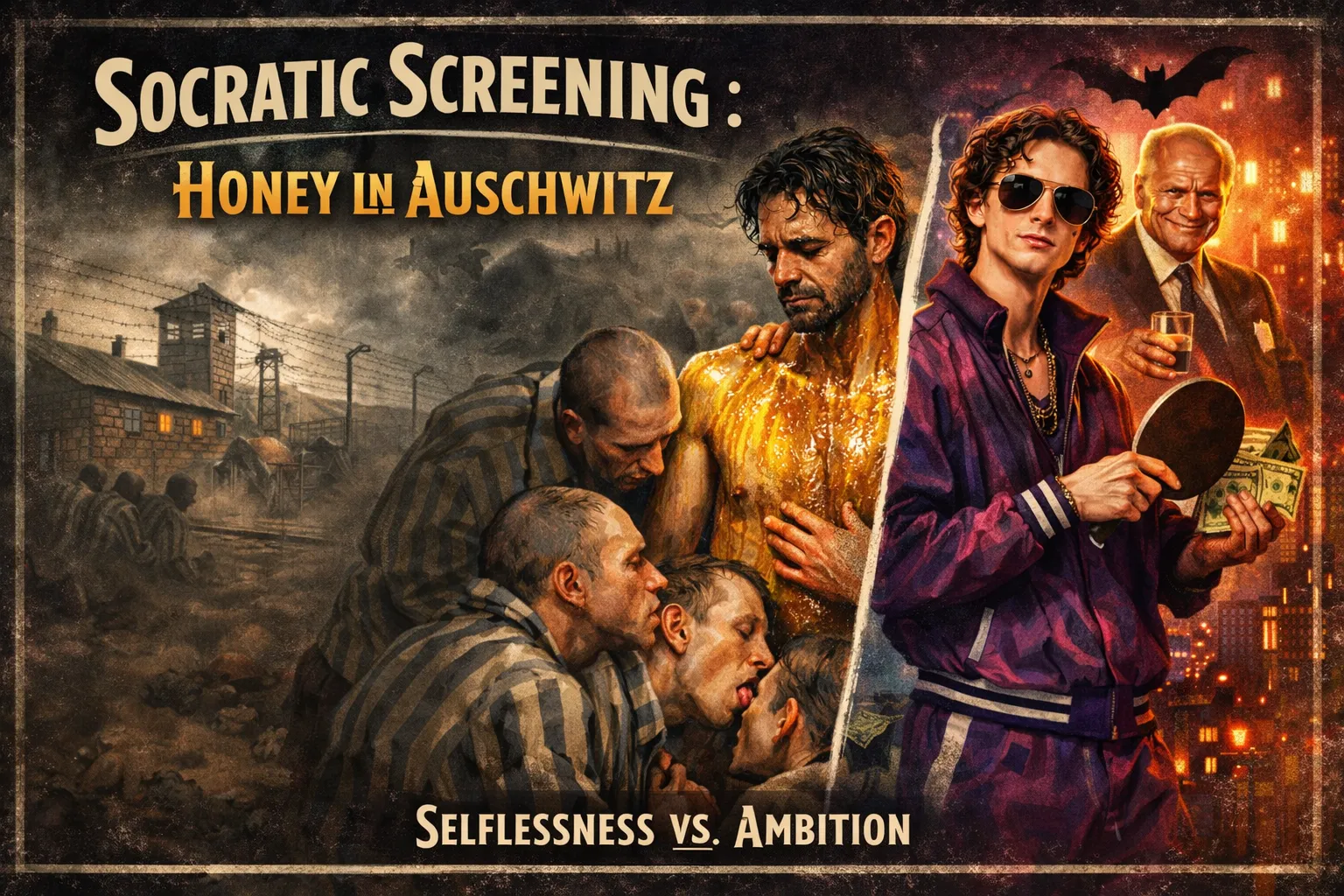

In Marty Supreme, there’s this really striking and unexpected flashback early on that stops the movie’s wild momentum dead in its tracks. Marty and his friend Béla Kletzki — a seasoned Hungarian Jewish table tennis player and Holocaust survivor — are in a room with Milton Rockwell, a wealthy benefactor type. When Milton learns Béla survived the camps, Béla tells one of the most intense stories in the film: while imprisoned at Auschwitz, he was sent out into the woods around the camp to disarm unexploded bombs for the Nazis. On one of these dangerous missions, he came upon a beehive. He used the honey he found there to help fellow prisoners survive starvation. Instead of keeping it for himself, he smeared the honey all over his body, smuggled it back into the barracks, then let the other starving inmates lick it off him to gain whatever nourishment they could. The cinematography lingers on the honey glistening, the visceral close-ups of tongues and the shared desperation for even that tiny bit of sweetness, and the whole thing unmoors the audience because it’s so raw and unfamiliar. The scene is beautifully weird and haunting, a quiet moment of selflessness amid horror that stands in stark contrast to Marty’s own relentless, self-centered hustle. The Forward

The honey flashback in Marty Supreme isn’t just shock value or surreal imagery. It’s a moment that carries three deep, intertwined meanings that resonate through the rest of the film. The Forward

First, it’s about humanity in the most dehumanizing circumstances. The act of smearing honey over one’s body so starving prisoners can lick it off isn’t meant to be elegant or pretty. It’s a visceral picture of extreme hunger, solidarity and sacrifice — one prisoner using the tiny resource he found not for himself, but to help others survive. That’s what the filmmakers and critics are pointing to when they call it a story of camaraderie and selflessness amid horror, and not just weirdness or a grotesque joke. The Forward

Second, the scene anchors Marty’s personal story. The film takes place only a few years after the Holocaust, and Jewish identity, trauma, survival and pride are part of Marty’s cultural and emotional backdrop. The honey story — told by Béla, a real survivor and former champion — is almost the antithesis of Marty’s brash self-mythologizing. While Béla’s tale is about communal care and what it takes just to live through unspeakable conditions, Marty’s journey starts as a self-centered quest for glory. By placing this flashback early on, the film contrasts true sacrifice with self-aggrandizement. Hey Alma

Third, it’s an embodied metaphor. The honey isn’t just food. In that moment, it represents life, dignity and an astonishing kind of generosity. It’s stark and sensory — something you feel in your gut rather than your head. That sensory impact underscores how the past — personal and collective — shapes Marty’s world, even as he tries to outrun it with hustle, hype and ambition. If you watch the rest of the film with that in mind, that scene becomes a kind of “core memory” of Jewish survival and identity that shadows Marty’s own arc. The Forward

So here’s the bottom line: the honey isn’t there to be funny or just grotesque. It’s a symbol of shared survival under extreme oppression, a counterpoint to Marty’s later choices, and a visceral reminder that history isn’t abstract. It has bodies, hunger, and moments of tenderness that are as strange as they are profound. The Forward

In Marty Supreme that honey flashback isn’t just a weird cinematic detour — it’s a moral lightning rod set deep into the story’s emotional soil. The way Béla’s memory is woven into the film creates a contrast, almost a foil to Marty’s relentless, ego-driven arc.Hey Alma

Béla’s story — about rubbing honey all over his body so fellow Auschwitz prisoners could lick it for nourishment — comes from a real tale about Hungarian Jewish table tennis champion Alojzy Ehrlich and is meant to embody selflessness, shared survival, and human generosity under extreme dehumanization. It’s a moment of communal care that, visually and thematically, feels almost like a bit of sacred imagery amid horror. The honey isn’t shock for its own sake, but a symbol of life offered to others even when there’s barely anything left.The Forward

Now, place that beside Marty: he’s brash, hungry for fame, scrambling up ladders and running roughshod over conventions, norms, even relationships in pursuit of his dream. He lies, hustles, steals, and constantly talks about what he deserves or what the world owes him. His drive is personal, almost self-worshipping at times. He’s obsessed with pedigree and proving himself as a Jew in a world that’s shown Jewish people unspeakable horrors, but he channels that into self-mythologizing, not communal care.Unpacked

That makes Béla’s honey flashback function like a mirror held up to Marty’s psyche. The survivor’s act is not about narrative swagger or grandstanding — it’s about giving his own body’s sweetness to others in a moment of shared desperation. Marty’s achievements, by contrast, are all about what he can claim for himself. Where Béla’s story is communal, Marty’s journey starts out as deeply individualistic. His achievements aren’t framed as gifts to others, they’re trophies to self.Hey Alma

In storytelling, when we talk about a foil it’s someone whose qualities highlight something in the protagonist by difference. Béla’s self-sacrifice and quiet endurance illuminate Marty’s relentless ambition and ego. Where Béla gives sweetness to others, Marty chases sweetness for fame, attention, and self-validation. That contrast turns the flashback into a moral compass — an emotional axis that helps us see Marty’s choices in sharper relief. It’s no accident that this memory of shared survival is one of the few deeply still, almost reverent moments in a film full of noise and youthful disruption.Vulture

In some readings, that comparison also helps explain why audience reactions are so divided: some laugh because the imagery is jarringly strange, and others are moved because they sense it’s pointing to something bigger than the spectacle. The honey isn’t just weird; it’s meant to be a mythic, sensory story about what it means to give life to others, and it pushes back against Marty’s self-centered hustle in a way you carry with you through the rest of the film.jewishpostandnews.ca

What Does the Auschwitz Flashback in ‘Marty Supreme’ Mean?🔗

This is a smart take, and it’s circling something real. Let me do a close read and then sharpen the foil idea, because that’s where the scene really clicks 🧠🍯

The honey story functions like a moral still frame inside a movie that otherwise never stops moving. Marty Supreme is all velocity, adaptation, hustle, shape-shifting. Marty survives by motion. The flashback, by contrast, is about stopping, sharing, and being used by others in the most literal, bodily way possible. That contrast is not incidental. It’s structural.

Béla’s act is radical because it turns the body into a commons. Honey on the chest is nourishment, but also dignity and vulnerability. He does not hoard it, monetize it, or leverage it for advantage. He becomes a surface others are allowed to take from. In extremis, he chooses collective survival over individual distinction. The story is almost anti-narrative. There’s no “and then I escaped,” no triumph arc, no branding. Just sustenance passed mouth to mouth in the dark.

Now put that next to Marty.

Marty’s body is also constantly being used, but in the opposite direction. He offers himself up to power, not to peers. He submits to Milton. He tolerates humiliation. He assimilates, adapts, sheds whatever makes him particular so he can keep moving upward. His suffering is transactional. Pain is a toll paid for momentum. When Milton spanks him, Marty accepts it as the price of admission to the next room. That’s not selflessness. It’s instrumental endurance.

So yes, Béla is a foil, but not in the simple “good man / bad man” sense. He’s a counter-ethic.

Béla represents an older Jewish moral logic shaped by scarcity and catastrophe: survival as mutual obligation. Marty represents a postwar, post-immigrant logic: survival as personal optimization. One pauses to share. The other accelerates to escape. One gives sweetness away. The other learns how to extract it from systems, rooms, people.

The Vulture piece nails something subtle when it notes that Marty may admire Béla’s story and simultaneously see it as what “holds him back.” That’s crucial. From Marty’s worldview, Béla’s generosity is beautiful but inefficient. Noble, but non-scalable. The kind of thing that doesn’t win championships or empires. In Marty’s universe, goodness doesn’t compound.

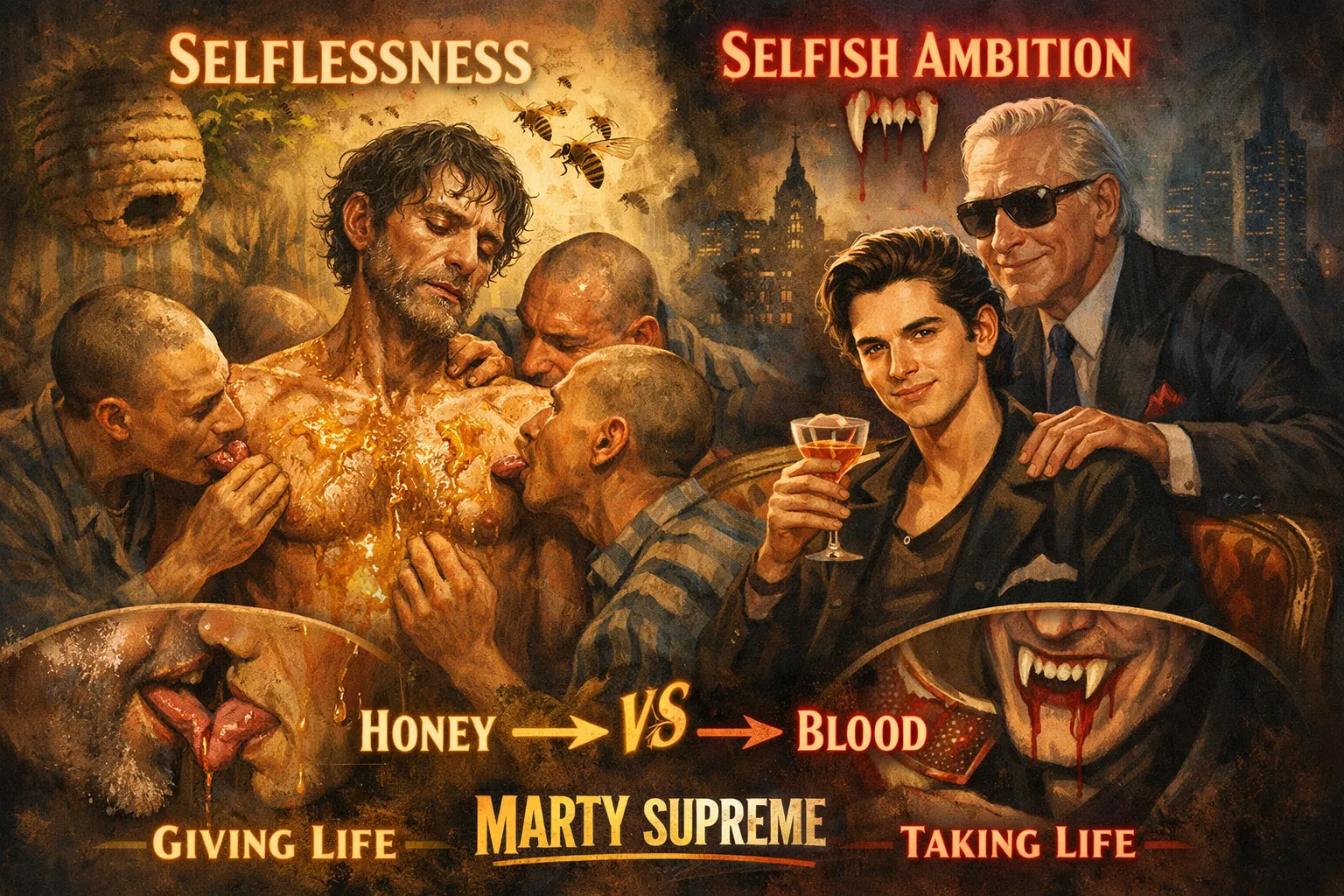

That’s why the vampire metaphor matters so much. Milton calls himself a vampire, and the film doesn’t correct him. Vampires feed. They extract vitality without giving it back. Béla does the inverse. He lets others feed on him. Honey versus blood. One is sweetness freely offered. The other is life forcibly taken. Marty is learning how to survive in a vampire economy.

And the reason the honey scene “unlocks the whole movie” is that it gives you the yardstick by which to measure Marty’s arc. The film never turns Marty into Béla. That would be sentimental and dishonest. Instead, it gives him one moment at the end where motion finally stops. With his child, he stands still. For the first time, something exists that is not a rung or a room or a hustle. Something that demands care rather than performance.

That moment doesn’t redeem Marty retroactively. It just cracks him open enough for Béla’s ethic to flicker into view. The honey story isn’t a lesson Marty learns. It’s a truth the film holds nearby, waiting to see whether Marty will ever grow large enough to live inside it.

What makes the scene unsettling, and why it lingers, is that the film never tells you which ethic wins. It just shows you the cost of each, and lets them coexist in the same body, the same history, the same restless, postwar world.

Josh Safdie Confirms Marty Supreme Almost Ended in Vampires🔗

Yes, this “vamping” thread actually tightens the whole argument, and in a very Safdie way 😈🩸

What that Vulture piece reveals is that the vampire idea isn’t a stray metaphor someone noticed after the fact. It’s a near-literal skeleton key for the movie. Safdie almost ended Marty Supreme with actual vampires because the logic was already there: who feeds on whom, and who consents to being fed on.

Seen through that lens, the honey scene becomes the movie’s ethical negative image.

Vampires take without permission. They extract life, energy, sweetness, and leave a body behind. Béla does the opposite. He offers himself up, knowingly, vulnerably, in a way that costs him something. His body becomes nourishment by consent. That’s why the image is so intimate and so unsettling. It’s not just generosity, it’s anti-predation.

Milton naming himself a vampire is one of those moments where Safdie lets the subtext walk onstage and introduce itself. Milton feeds. On labor, on ambition, on Marty’s willingness to endure humiliation. Marty understands this instinctively. He doesn’t resist it. He doesn’t moralize it. He bargains with it. Marty’s genius isn’t goodness, it’s adaptability to predation. He learns how to survive inside a vampire ecosystem without being killed outright.

That’s the crucial distinction between Marty and Béla as foils.

Béla’s story comes from a world where the worst thing imaginable has already happened, and the only remaining question is whether people will help one another live through it. Marty’s world is one where the worst thing hasn’t happened yet, but could, and the game is to stay ahead of it at all costs. Béla pauses and shares. Marty moves and absorbs.

The near-vampire ending makes clear that Safdie sees capitalism, assimilation, and postwar hustle as soft supernatural horror. No fangs required. Just people who know how to drain rooms faster than others can replenish themselves. Marty isn’t a vampire, but he is vampire-adjacent. He’s someone who learns how to offer his neck strategically, how to let himself be fed on so he can keep climbing.

That’s why the spanking scene, as grotesque as it is, fits perfectly into this schema. It’s ritualized submission to power. Marty accepts pain as payment. Vampires don’t just feed, they dominate. Marty survives by consenting to domination in exchange for access.

And this is where the ending lands with surprising restraint.

When Marty meets his child, the movie briefly imagines a different economy. Not feeding. Not hustling. Not extraction. Just standing still in the presence of something that can’t be leveraged without becoming monstrous. The baby can’t feed him anything yet. Marty has to give without return. That’s Béla’s ethic, flickering back into the story at the very end.

Safdie almost ending with vampires tells you how dark the underlying vision is. Choosing not to do it tells you what he’s actually interested in: not condemning Marty, not redeeming him, but showing how easily a human learns to live among vampires, and how rare it is to remember another way of surviving.

The honey scene is the proof that another way once existed. The vampire theme is the proof of how far the world has drifted from it.

Claude

The scene is a flashback where Béla Kletzki (Géza Röhrig) tells his Auschwitz story. The Nazis recognized him as a table tennis champion and spared him to defuse bombs in the woods outside the camp. During one mission, he found a beehive, smoked out the bees with a cigarette, stripped naked, and smeared honey all over his body. He then dressed and returned to camp, where his fellow prisoners licked the honey directly off his skin for nourishment.

It’s shot in close-up like a Renaissance painting, with honey glistening on Röhrig’s chest and torso. The scene shows multiple prisoners licking the honey off him en masse.

The moment has sparked intense debate... some viewers laugh (probably from discomfort with the absurd imagery), others are moved to tears. It’s become the most talked-about scene in the film.

Based on a true story: the real Alojzy “Alex” Ehrlich, a Polish Jewish ping-pong champ who survived four years at Auschwitz, actually did this. It’s documented in Marty Reisman’s autobiography. Safdie calls it a “beautiful story” about camaraderie in the camps, though the visceral imagery makes it hard to process.

What Does the Auschwitz Flashback in 'Marty Supreme' Mean?🔗

That’s a sharp reading. A few things that stand out:

The vampire/honey opposition — Milton literally calls himself a vampire later in the film. Perfect inversion of what Béla did... one takes life force from others, the other gives the sweetness of his own body. That’s a really elegant observation.

Why Marty might admire but not learn from the story — The line about Marty seeing it as “both the ultimate mitzvah and a sign of what holds Béla back from greatness as an individual player” cuts right to it. Marty respects the act but fundamentally can’t adopt the mindset. Stopping and sharing is antithetical to his entire approach.

The motion vs. stillness theme — “The world runs on those who go fast, break walls, and never look back” versus Béla’s act of “stopping, pausing, and sharing.” The whole film is about Marty’s relentless forward momentum, his willingness to sacrifice dignity to keep hustling. The honey scene is the opposite energy entirely.

Jewish assimilation — Marty sublimating his Jewish self to enter goyish spaces (the Ritz, Waspy bowling alleys, uptown soirées). He maintains Jewish identity culturally but has zero interest in tradition or collective responsibility. Makes the Milton spanking scene even more loaded... he takes the humiliation to preserve his ability to keep climbing.

The ending where he finally stops still, holding his newborn, makes more sense now. First time something exists beyond his own ambition.

Comments

Join the discussion on GitHub.