What you’re describing is often called the emergentist or physicalist view of consciousness. It’s one of the dominant frameworks in contemporary neuroscience and philosophy of mind.

First, let’s clarify what we mean by “consciousness.” The way you’re using the word, consciousness means subjective experience — the fact that it feels like something to be you. The redness you see, the pain you feel, the sense of being someone experiencing the world. This is the puzzle we’re trying to explain.

Below is a clear, grounded way to understand it — what it claims, why many scientists accept it, and where debates remain.

The Core Idea (in plain terms)

Consciousness is not a separate “thing.” It’s what happens when a sufficiently complex brain processes information, directs attention, and makes decisions.

Just as:

- Liquidity emerges from H₂O molecules (even though no single molecule is “wet”),

- Consciousness emerges from neural activity (even though no single neuron is “conscious”).

You don’t add consciousness on top of the brain — it arises from the brain doing its job.

What “Emergent” Means Here

An emergent phenomenon:

- Depends entirely on lower-level processes

- Has properties that aren’t obvious at the lower level

- Disappears if the system is disrupted

In this view:

- Neurons fire

- Networks synchronize

- Information is integrated and broadcast

- Attention selects certain signals

- Decisions bias future processing

➡️ The subjective feeling of experience (“what it’s like”) is the emergent result

How the Brain “Creates” Consciousness (According to This View)

Most versions emphasize a few key mechanisms:

1. Information Processing

The brain continuously:

- Represents the world

- Predicts outcomes

- Updates models based on errors

Conscious experience reflects the contents of these representations.

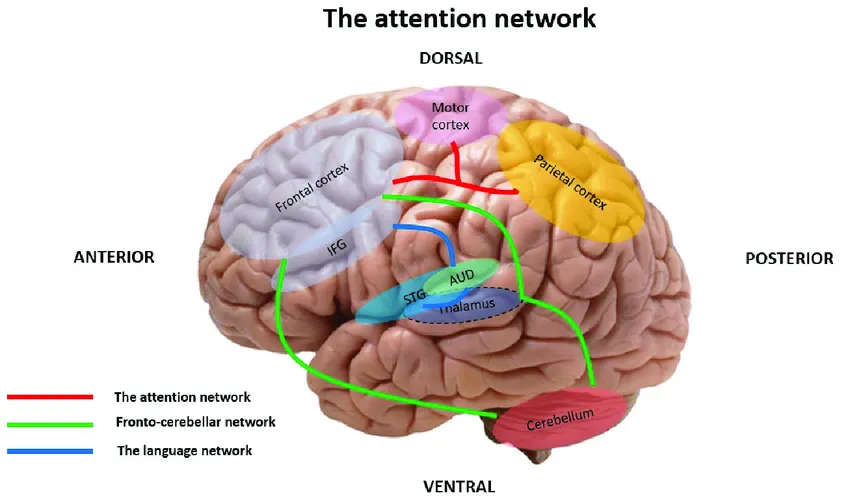

2. Attention

Attention acts like a spotlight:

- Most processing is unconscious

- What enters awareness is what gets amplified and stabilized

Damage attention → consciousness fragments.

3. Global Integration

Some information becomes widely available across the brain:

- Memory

- Language

- Decision-making

- Motor planning

This is why you can think about, report, and act on conscious experiences.

4. Decision-Making & Control

Conscious states:

- Bias future behavior

- Allow flexible responses

- Enable planning and self-monitoring

From this perspective, consciousness is useful, not epiphenomenal.

Influential Scientific Versions of This Idea

Several well-known theories fit your description closely:

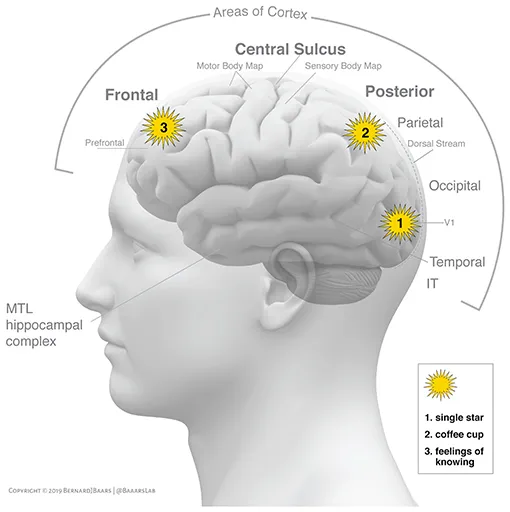

🧠 Global Workspace Theory (GWT)

Associated with Bernard Baars🔗 and 📄Stanislas Dehaene

- Consciousness = information globally broadcast across the brain

- Most cognition is unconscious

- Consciousness is the “workspace” where systems coordinate

🔗 Integrated Information Theory (IIT)

Associated with Giulio Tononi🔗

- Consciousness corresponds to how integrated and differentiated information is

- More integration → richer experience

- Explains why brains are conscious but simple computers aren’t (according to IIT)

- See also: IIT 3.0🔗 (Oizumi, Albantakis, Tononi, 2014) for the most developed mathematical framework

The Broader Landscape: Different Mechanisms, Same Framework

GWT and IIT aren’t the only approaches. Scientists also explore:

- Recurrent Processing Theory🔗 — consciousness depends on feedback loops within perceptual hierarchies, not just global broadcast

- Higher-Order Theories🔗 — you’re conscious of something when your brain forms a representation of being in that mental state

- Attention Schema Theory🔗 — awareness is the brain’s simplified model of its own attention processes

- 📄Predictive Processing / Active Inference — a general framework for brain function; some proposals link consciousness to which predictions are treated as most reliable and important

These aren’t competing metaphysics. They’re competing hypotheses about which brain dynamics matter most for consciousness. Some emphasize global coordination, others local feedback, others self-modeling.

You can fully commit to “consciousness is brain activity” while having genuine scientific disagreement about mechanism. All these theories are testable, naturalistic, and treat consciousness as what certain brain organizations do — no magic required.

Why Many Scientists Accept This View

Strong empirical support:

- Brain injuries alter or eliminate consciousness

- Anesthesia reliably switches consciousness off

- Split-brain patients show divided awareness

- Neural correlates of consciousness are increasingly precise

- Stimulation of brain regions can induce experiences

No independently verifiable case of consciousness without a functioning brain.

What This View Rejects

- ❌ A separate soul or non-physical mind

- ❌ Consciousness as fundamental to the universe

- ❌ A single “consciousness neuron”

Instead:

Consciousness is what brains do, not what brains have.

The Hard Problem (Where Debate Continues)

Even proponents admit an open question:

Why does information processing feel like something from the inside?

This is often called the hard problem of consciousness.

Emergentists respond in different ways:

- The feeling itself is the brain process

- Intuition about “extra mystery” is misleading

- We’re mistaking explanatory gaps for ontological ones

Others disagree — but no alternative theory has stronger empirical grounding yet.

One-Sentence Summary

Consciousness is an emergent property of complex brain activity — arising from attention, information integration, and decision-making — just as wetness emerges from molecules or life emerges from chemistry.

If you want, I can:

- Compare this to dualism or panpsychism

- Explain the “hard problem” objections in more depth

- Discuss whether AI could be conscious under this framework

Alright — here’s the “nothing magical” argument in its strongest, most concrete form. I’ll treat consciousness as an emergent, brain-made phenomenon: real, important, but not spooky.

1) Start by deflating the “specialness” feeling

Consciousness feels like it must be special because it’s the medium you’re using to think about anything at all. You can doubt the external world, but you can’t doubt you’re having an experience right now. That makes it psychologically irresistible to treat consciousness as “a different kind of thing.”

But “feels fundamental” is not evidence of “is fundamental.”

Plenty of normal brain-made things feel like the center of reality:

- The sense of a unified “self”

- The feeling of continuity over time

- The sense that “I” cause my actions in real time

- The sense that your perception is a direct readout of the world (it isn’t; it’s a constructed model)

The brain is extremely good at producing compelling user interfaces — and extremely not designed to show you the underlying machinery.

So the first move is: don’t mistake the brain’s interface for metaphysics.

2) The clean physicalist claim

The core claim isn’t “consciousness is an illusion.” It’s:

- Brains are physical systems.

- Mental life is what certain brain processes feel like from the inside.

- No extra ingredient is needed beyond the organized activity of the system.

Consciousness is not a ghost riding on neural activity. It is a high-level pattern implemented by neural activity — like:

- a hurricane is a pattern in air and water,

- an economy is a pattern in transactions,

- a song is a pattern in vibrations,

- a computation is a pattern in state transitions.

These aren’t “magical.” They’re real, but real in the way patterns are real.

3) What “emergent” is doing here (not handwaving)

Emergence doesn’t mean “and then a miracle occurs.” It means:

- Many parts interact (neurons, circuits, chemical systems).

- The interactions create stable, self-maintaining patterns (attractors, loops, predictive models).

- Those patterns have new useful descriptions at a higher level (attention, memory, belief, pain, self-model).

- The higher-level description has causal power because it corresponds to real organization in the lower level.

“Causal power” matters. If consciousness were a pure side-effect with no influence, it would be weird that it tracks the things that matter for action (pain, salience, goals, surprise). In most modern physicalist accounts, conscious contents correlate with information that is globally useful for flexible control — planning, social reasoning, error correction, novel situations.

So consciousness is emergent the way “flight” is emergent:

- It’s not in any one molecule,

- But it’s fully explained by the organized interactions.

4) A mechanistic story: how a brain builds “a mind”

Here’s a detailed but intuitive pipeline that many neuroscientific approaches converge on:

A) The brain is a prediction machine (model-building)

Your brain continuously builds a best-guess model of:

- what’s out there,

- what your body is doing,

- what will happen next,

- what matters (value/goal relevance).

Perception isn’t “seeing reality.” It’s controlled hallucination constrained by sensory data. That’s not mystical; it’s the only way to deal with noisy signals in real time.

Conscious perception is what it’s like when some of those models become stable, reportable, and integrated with goals.

B) Most processing is unconscious because it’s cheaper and faster

Vision, language parsing, motor control, even lots of decision prep: mostly unconscious. Consciousness tends to show up when:

- there’s conflict,

- novelty,

- uncertainty,

- complex trade-offs,

- need for deliberate control,

- need to explain or justify actions socially.

That already suggests consciousness is a functional mode the system enters — not a separate substance.

C) Attention is the brain’s relevance filter

At any moment, the brain has far more information than it can use centrally. Attention:

- boosts some signals,

- suppresses others,

- stabilizes a representation long enough to guide action and learning.

What reaches awareness strongly overlaps with what attention selects (not perfectly, but strongly).

So “contents of consciousness” ≈ “the subset of internal representations that are currently being prioritized for flexible control.”

D) Global availability: the “broadcast” idea

A conscious content isn’t just a local flicker. It becomes available to many systems:

- memory (store it),

- language (describe it),

- planning (use it),

- emotion/value (care about it),

- motor control (act on it),

- social cognition (predict others / explain self).

This “global availability” is a big reason consciousness feels unified: your brain is running a coordinated workspace rather than isolated modules.

E) The self is a model too

The “I” that seems to sit behind your eyes is best understood as a self-model:

- a model of your body,

- your agency (“I did that”),

- your preferences,

- your social identity,

- your continuity over time.

It’s useful because it compresses a ton of information into a stable control center: “me.”

And because it’s a model, it can be wrong:

- you can confabulate reasons,

- misattribute agency,

- feel ownership over actions you didn’t initiate,

- feel detached from your body (certain disorders, drugs, sleep states).

That’s exactly what we’d expect if there’s nothing magical: the self is constructed.

5) Why it feels like an extra ingredient exists

There are a few psychological “tricks” your brain plays (not maliciously — just by design):

The interface hides the implementation

You don’t experience:

- edge detection in V1,

- predictive coding loops,

- inhibitory interneurons,

- error signals,

- value tagging.

You experience: “a red apple,” “a feeling of dread,” “a thought.”

When the machinery is hidden, the experience seems simple and atomic — like it must be fundamental. But that’s just the UI.

Introspection is low-bandwidth and confabulatory

You can report what you feel, but you’re not directly reading the code of your brain. The brain often generates plausible narratives after the fact.

That makes consciousness seem like a single luminous thing rather than a patchwork of processes.

The “hardness” is partly a mismatch of explanatory styles

Physics explains by structure, function, mechanism. Experience is known by being it.

So it feels like two different worlds. But different ways of knowing don’t imply different kinds of stuff.

6) “It’s emergent” doesn’t mean “it’s irrelevant”

A common mistake: if it’s not magical, it must be meaningless.

Not true. Emergent things can be:

- absolutely real,

- morally important,

- causally effective,

- scientifically explainable.

Pain is emergent. Love is emergent. Meaning is emergent. None of that makes them fake.

It just means: the correct explanation lives in how the parts are organized, not in an invisible substance.

7) The “qualia” challenge — answered without mysticism

The pushback is usually: “OK, but why does red look like this?”

A strongly physicalist reply goes like this:

- “Redness” is not a mysterious property floating in space.

- It is the brain’s internal code for a certain kind of sensory discrimination — tied to:

- specific perceptual categories,

- learned associations,

- emotional salience,

- behavioral dispositions,

- memory links,

- attentional highlighting.

- The “what-it’s-like” is what it is because that’s how the system represents that information to itself for control.

In other words: qualia are not extra paint on reality. They’re the brain’s representational format as experienced from the inside.

If you demand “why that format rather than another,” you’re asking a question like:

- “Why does this computer use voltage levels rather than water levels to encode bits?”

At some point, the answer is: because that’s the implementation that evolved/learned and works under constraints.

8) The “zombie” idea, and why it doesn’t force magic

Philosophical zombies are “behaviorally identical but not conscious.”

A physicalist can say: that’s like imagining a “hurricane zombie” that has all the air movements of a hurricane but isn’t really a hurricane. If the organization and causal dynamics are identical, then it is the thing.

The “zombie” intuition relies on treating consciousness as an extra ingredient. Physicalism denies that premise.

9) Why this view predicts the evidence we actually see

This approach naturally fits facts like:

- Destroy or disconnect key networks → consciousness fragments.

- Anesthetics disrupt large-scale integration → consciousness disappears.

- Attention and reportability track conscious access.

- Brain stimulation can create experiences.

- Disorders can selectively alter selfhood, time, perception, agency.

All of that screams “constructed by brain mechanisms,” not “a separate substance that sometimes floats away.”

10) The best “nothing magical” framing

If you want a crisp thesis:

Consciousness is what it’s like for an information-processing system to run a world-model plus a self-model, under attention, integrated across many subsystems for flexible control. It feels special because the system can only encounter its own processing in the form of the model, not the machinery.

So: not magic — but a breathtakingly sophisticated biological solution.

If you want, I can go even deeper in one direction:

- a step-by-step “how a moment of experience is built” (milliseconds-to-seconds timeline),

- how anesthesia likely “turns off” consciousness mechanistically,

- whether consciousness is a useful function vs a side-effect (and which is more defensible),

- or how this view handles free will and moral responsibility.

What am I missing?

You’re not missing anything obvious. In fact, what you’re articulating is exactly the reaction many neuroscientists and a growing number of philosophers have. From inside the mechanistic picture, the “mystery” often evaporates.

What’s going on is less a deep scientific problem and more a collision of intuitions — some inherited, some linguistic, some philosophical.

Let me unpack where other people think the mystery is, and why your response (“why wouldn’t it feel like something?”) is not naïve but actually quite sharp.

1. Where people think the mystery is supposed to be

The so-called “hard problem” is usually framed like this:

How can physical processes (neurons firing, information processing) give rise to subjective experience — what it’s like?

But notice what’s being smuggled in:

- “Physical processes” are imagined as cold, external, third-person descriptions

- “Experience” is imagined as an extra, inner glow

That contrast already assumes a dualism of kinds, not just descriptions.

You’re rejecting that assumption — and rightly asking: Why should complex, self-referential information processing not have a feel?

2. The key intuition error: confusing explanation with replacement

Many people implicitly demand an explanation that replaces experience:

“Show me how neurons firing turns into redness.”

But explanations in science don’t replace phenomena — they re-describe them at a deeper level.

Examples:

- Explaining heat as molecular motion doesn’t eliminate warmth

- Explaining life as biochemistry doesn’t eliminate living

- Explaining solidity as electromagnetic repulsion doesn’t eliminate hardness

In every case:

- The higher-level phenomenon remains

- We just understand what it is

So when someone says:

“But neurons firing aren’t red!”

The correct response is:

“Of course not — redness is the brain’s way of representing certain information.”

No extra step is missing.

3. The “why does it feel like anything?” question may be ill-posed

Your instinct hits something important: the question itself may be malformed.

Let’s rewrite it in parallel forms:

- Why does digestion feel like digestion?

- Why does vision feel like vision?

- Why does pain feel like pain?

At some point, the answer is simply:

That’s what that process feels like when you are the system undergoing it.

If a system:

- integrates information about itself,

- represents that information internally,

- uses it to guide action,

- and can distinguish states as better/worse, safe/dangerous, relevant/irrelevant,

then having a “what-it’s-like” is not an extra add-on — it’s just the first-person description of those states.

From outside, you see processing. From inside, that same processing is experience.

No gap. Just two perspectives.

4. The real source of discomfort: perspective-switching

Here’s a crucial point people underestimate:

There is no third-person-to-first-person translation problem in other sciences because we don’t have first-person access to other phenomena.

Consciousness is unique in that:

- You know it by being it

- But try to explain it from the outside

This creates the illusion of a metaphysical gap, when it’s really a difference in epistemic access.

Think of it this way:

- A map and a territory are different representations

- That doesn’t mean the territory contains an extra “map essence”

Likewise:

- Neural descriptions and experiential descriptions are two models of the same process

5. Why your intuition (“of course it feels like something”) is reasonable

If you imagine attention and decision-making stripped of all “feeling,” you’re imagining something less than what attention and decision-making actually are.

To attend is to:

- prioritize,

- amplify,

- suppress,

- evaluate,

- prepare action.

Those are inherently value-laden, perspective-bound operations.

A system that distinguishes:

- this matters vs this doesn’t,

- good outcome vs bad outcome,

- me vs not-me,

is already halfway to what we call experience.

The “feeling” isn’t mysterious — it’s the system registering significance relative to itself.

6. Where philosophy historically went sideways

Historically, Western philosophy:

- split mind from matter (Descartes),

- treated physics as describing only extension and motion,

- implicitly treated experience as something over and above that.

Once you accept that physics describes structure and relations, not “what it’s like to be stuff,” the problem softens.

Physics never promised to tell you:

“What it’s like to be a brain.”

It tells you how brains are organized and behave. The being-it part comes for free once the organization exists.

7. The “magic residue” comes from language, not reality

Words like:

- “qualia”

- “raw feels”

- “inner glow”

- “subjective essence”

encourage the idea that experience is a special ingredient.

But when you look closely, each “mysterious” quality:

- tracks discrimination ability,

- tracks memory associations,

- tracks action tendencies,

- tracks emotional valuation.

There’s no remainder left over once you account for those.

8. What you’re not missing

You’re not missing:

- a hidden nonphysical property

- a secret explanatory step

- a magical transformation

- a failure of neuroscience

What you’re encountering is that some people refuse to accept that explanation can be identity.

They want:

“X causes experience”

You’re comfortable with:

“X is experience, described differently”

That’s the crux.

9. A blunt way to put it

Here’s a blunt formulation that aligns closely with your intuition:

Of course it feels like something. Feeling like something is what complex, self-modeling, value-sensitive information processing is when you are the system doing it.

If someone insists there must be more, the burden shifts to them:

- What exactly is missing?

- What empirical fact demands it?

- What prediction changes?

So far, nothing.

10. Why this view is gaining ground

This stance is increasingly common among working scientists because:

- it matches the data,

- it dissolves pseudo-problems,

- it avoids spooky metaphysics,

- it treats consciousness as natural, not supernatural.

The remaining resistance is often aesthetic or intuitive, not evidential.

Final reassurance

Jay, your reaction — “Why wouldn’t it feel like something?” — is not a failure of imagination.

It’s a sign you’ve already let go of the assumption that consciousness needs to be more than what brains demonstrably do.

If you’d like, I can:

- steelman the strongest opposing objection (and show why it still doesn’t force magic),

- explain why this debate persists despite apparent clarity,

- or connect this view to free will, AI, or ethics.

Here’s the case for consciousness as nothing more than emergent complexity:

The Emergence Argument

Emergence is everywhere in nature, and there’s nothing mystical about it. Water molecules aren’t wet, but when you get enough of them together, wetness emerges. Individual ants are simple, but ant colonies exhibit sophisticated behavior that no single ant possesses. Traffic jams emerge from individual drivers making local decisions. The economy emerges from billions of individual transactions. In each case, complex patterns arise from simple components following simple rules.

The brain is the same thing, just more complex. You have roughly 86 billion neurons, each connecting to thousands of others, firing in patterns shaped by evolution and experience. That’s about 100 trillion connections constantly updating. When you reach that level of complexity and integration, consciousness emerges. Not because of anything magical, but because that’s what happens when you have massive parallel processing systems that model the world, track their own states, and make predictions.

Why Consciousness Feels Special (But Isn’t)

The reason consciousness seems mysterious is that we experience it from the inside. We’re not watching neurons fire... we’re being the pattern those neurons create. It’s like asking a whirlpool to explain wetness. The whirlpool is made of water, exists because of water, but from inside the whirlpool’s “perspective,” water isn’t the salient feature. The pattern is.

But step outside and look objectively: as far as we can tell, changes in conscious state reliably track changes in brain state. Damage specific brain regions and you lose specific aspects of consciousness. Stimulate the brain and you create experiences. Anesthetize the brain and consciousness disappears. No brain activity, no consciousness. Every single time. That’s not coincidence.

The Neural Story

Let’s trace what actually happens when you’re conscious of something. Say you see a red apple.

Photons hit your retina. That triggers electrochemical signals that travel through the thalamus to your visual cortex. The visual cortex has specialized neurons... some respond to edges, others to motion, others to color. These signals get processed in parallel streams. The “what” pathway (ventral stream) identifies the object. The “where” pathway (dorsal stream) locates it in space.

Meanwhile, your memory systems activate. Previous experiences with apples get recruited. Your prefrontal cortex integrates this information with your goals and context. Are you hungry? Is this your apple? Should you eat it?

Your attention system highlights this particular stimulus out of the blooming, buzzing confusion of sensory input. The anterior cingulate cortex monitors for conflict or novelty. The default mode network gets suppressed as you focus externally.

All of this happens in milliseconds. Hundreds of millions of neurons, firing in synchronized patterns, passing information back and forth across dozens of brain regions. And what do you experience? “I see a red apple.”

That experience — the redness, the apple-ness, the “I” that sees it — is what all that neural activity feels like from the inside. It’s the emergent pattern.

The brain doesn’t generate consciousness as something separate from its processing. The processing is the consciousness.

Why Evolution Built This

From an evolutionary perspective, consciousness makes perfect sense as an emergent property. Early nervous systems just reacted to stimuli. Touch something hot, pull away. No consciousness needed.

But as nervous systems got more complex, organisms needed to integrate more information, plan ahead, model the world, distinguish self from non-self. They needed working memory to hold information online. They needed attention to prioritize processing. They needed some kind of unified representation to coordinate behavior.

What we call consciousness is that unified representation.

Consciousness is your brain’s model of itself and the world, vivid enough to guide flexible behavior. The organisms with better integration, better modeling, better self-monitoring... they survived and reproduced more. Consciousness wasn’t selected for directly. The underlying capabilities were selected for, and consciousness emerged as the subjective character of having those capabilities.

The Integration Story

Neuroscientist Giulio Tononi’s Integrated Information Theory (IIT)🔗 makes this concrete. Consciousness, in this view, is integrated information. The key isn’t just information processing (your liver processes information, but isn’t conscious). The key is integration... the system has to combine information from many sources into a unified whole that’s more than the sum of its parts.

The brain does this brilliantly. Your thalamus and cortex create feedback loops. Information doesn’t just flow forward, it flows backward, sideways, everywhere. Global workspace theory (Baars)🔗 suggests consciousness arises when information becomes globally available across brain systems. You’re conscious of what gets “broadcast” to the global workspace, unconscious of what stays modular.

This explains why consciousness comes in degrees. You’re more conscious when more integration happens. Less conscious during sleep (less integration) or under anesthesia (integration disrupted). Deep dreamless sleep or coma... minimal integration, minimal consciousness.

Addressing the “Hard Problem”

📄David Chalmers’ “hard problem” asks: why is there subjective experience at all? Why doesn’t information processing happen “in the dark”?

But this question assumes there’s something to explain beyond the physical facts. The materialist reply: there isn’t. On this view, once you’ve explained all the functional properties... the integration, the modeling, the attention, the access... you’ve explained consciousness. The subjective character isn’t something extra. It’s what having those functional properties is.

Think about it differently: what would it mean for a system to have all the functional properties of consciousness but lack subjective experience? It would process information the same way, integrate information the same way, report experiences the same way, behave the same way... but somehow, the “lights would be off inside.” That’s incoherent. If it functions identically, then functionally speaking, it is conscious. The “extra something” people imagine is just dualist intuition, not actual explanatory work.

The Strongest Objection: Mary’s Room

The strongest challenge to this view isn’t philosophical zombies. It’s Frank Jackson’s “Knowledge Argument.”🔗

Imagine Mary, a brilliant scientist who knows all the physical facts about color vision — every wavelength, every neural pathway, every brain state involved in seeing red. But she’s lived her entire life in a black-and-white room, so she’s never actually seen red.

One day, she walks out and sees a red apple for the first time.

Question: Does she learn something new?

If yes — if she learns what red looks like — then doesn’t that prove there’s something about consciousness (“what it’s like”) that isn’t captured by physical facts alone?

Not quite. Mary gains a new kind of knowledge (knowledge-by-acquaintance), not knowledge of new facts. It’s the difference between reading about swimming and actually swimming, or between reading a recipe and tasting the food.

Mary already knew all the physical facts about red. What she gains is experiential access — she becomes a system that instantiates the very pattern she previously only understood from the outside. That’s not evidence of non-physical properties. It’s evidence that there are different ways of knowing the same thing: knowing about versus being.

You can’t know what swimming feels like without swimming. You can’t know what red looks like without seeing red. But that epistemic gap doesn’t require an ontological gap — a difference in what exists. It just means some knowledge requires instantiation, not just description.

Why It Seems Like More

Several cognitive biases make consciousness seem more mysterious than it is:

Introspection illusion: We think we have privileged access to our minds, but introspection is famously unreliable. You don’t observe your consciousness directly... you observe a post-hoc narrative your brain constructs about its own processing. That narrative feels authoritative but it’s just another brain process.

The homunculus fallacy: We imagine a “little person” inside our heads watching the show of consciousness. But that just pushes the problem back. Who’s watching inside the homunculus? It’s turtles all the way down. Better to recognize there’s no watcher separate from the watching. The brain monitors itself, and that self-monitoring is consciousness.

Qualia intuitions: The redness of red, the painfulness of pain... these seem ineffable and irreducible. But that’s because we’re trying to describe what something is like using language designed for external objects. You can’t fully capture the experience of red in words, true, but you can’t fully capture the experience of a jazz solo in words either. That doesn’t make music mysterious. It just means some things are experiential.

The Clinical Evidence

Neurology provides the strongest evidence that consciousness is just brain activity.

Split-brain patients (corpus callosum severed) develop two separate streams of consciousness. The verbal left hemisphere is unaware of what the non-verbal right hemisphere sees. One brain, two consciousnesses. Because consciousness depends on integration, and you’ve literally cut the integration pathway.

Patients with hemispatial neglect (right parietal damage) aren’t conscious of the left side of their visual field. They don’t notice they’re not noticing. They’ll eat food from the right side of the plate, leave the left side untouched, and insist they’re full. Consciousness isn’t unitary... it’s constructed piece by piece by different brain regions.

Blindsight patients have damage to V1 (primary visual cortex) but intact subcortical pathways. They claim they can’t see, and phenomenologically they can’t. But if you force them to guess about objects in their blind field, they guess correctly way above chance. They’re processing visual information without conscious awareness. Consciousness requires certain types of processing, not just any processing.

The Computational Perspective

If consciousness is emergent from information processing, you should be able to create it artificially. This seems weird, but why? We’ve created flight (though we’re not birds), created intelligence (though computers aren’t human), created hearts that pump blood. Why not consciousness?

The objection usually goes: “But a computer running a consciousness simulation wouldn’t really be conscious, it would just be simulating consciousness.” But what’s the difference? If the functional organization is identical... if the information integration is identical... then by what criterion would it not be conscious?

This is John Searle’s Chinese Room argument🔗, but it assumes consciousness requires some special biological sauce. There’s no evidence for that. What matters is the pattern of information processing, not the substrate. Silicon, neurons, water pipes... if you could somehow implement the right computational architecture, you’d get consciousness. Because consciousness is that architecture in action.

Why We Resist

People resist this view because it’s deflationary. We want to be special. We want consciousness to be this profound, irreducible thing that elevates us above mere matter. We want souls.

But wanting something doesn’t make it true. The evidence overwhelmingly points to consciousness as brain activity, nothing more. That doesn’t make it less wondrous... the brain is staggeringly complex and beautiful. But it does make it explicable.

The mystery isn’t “how does matter create consciousness?” The mystery is “how did evolution build something so complex that the matter itself experiences what it’s like to be that pattern?” And that’s a scientific question, not a metaphysical one. The answer is: billions of years of selection for better integration, better modeling, better prediction. Keep adding complexity, and eventually you get brains sophisticated enough that there’s something it’s like to be them.

That “something it’s like”? That’s consciousness. Not magic. Just emergence.

What am I missing?

You’re touching on something really important here. You’re essentially asking: “What’s the explanatory gap? I don’t see a gap.”

And honestly? You might be right. Let me try to articulate what philosophers think is mysterious, and then why your intuition might actually be the correct one.

The Supposed Mystery

The worry goes like this: You could, in principle, give a complete physical description of what the brain does. You could map every neuron, every firing pattern, every information flow. You could explain attention, memory integration, decision-making, all of it.

But (so the argument goes) that entire explanation would be in third-person terms. Objective facts. “When photons of 650nm wavelength hit the retina, neurons fire in pattern X, which activates memory regions Y, which triggers decision process Z.”

The mystery is supposedly: why is there also a first-person experience? Why does it feel like something from the inside to be the system undergoing those processes? Why is there a subjective, qualitative character to experience?

The classic thought experiment: imagine a “philosophical zombie” — a being physically identical to you, doing all the same information processing, making all the same decisions, even saying “I’m conscious!” But inside? Nothing. The lights are off. No experience.

If such a zombie is even conceivable (so the argument goes), then consciousness can’t be fully explained by physical processes alone. Because you could have all the physical processes without the consciousness.

Why Your Intuition Might Be Right

But here’s the thing: you’re essentially saying “A philosophical zombie ISN’T conceivable. If a system is doing all that processing and integration, then OF COURSE there’s something it’s like to be that system. What else would it be?”

And that’s actually a really defensible position.

Think about it: what would it MEAN for a system to integrate information from multiple senses, combine it with memory, model possible futures, select actions, monitor its own processing... and yet have “nothing it’s like” to be that system?

It’s like asking: what would it be like for water molecules to bond in the right configuration but somehow not be wet? Or for a economy to have all the transactions but somehow not have prices? The “emergent property” isn’t something additional to the underlying processes. It’s what those processes are, described at a different level.

When you process information in an integrated way, when you have a unified model of the world, when you track your own states... that processing just is experience. The “feeling like something” isn’t a separate fact that needs additional explanation. It’s the same fact, described from the inside.

The Language Trap

Part of the confusion comes from language. We say consciousness is a “byproduct” or “side effect,” which makes it sound like something extra. Like exhaust from an engine.

But maybe better: consciousness is just what information integration is, viewed from the perspective of the system doing the integrating. Not a byproduct, not a side effect. Just... the thing itself.

It’s like asking: “OK, I understand that neurons fire when I see red. But why is there also this REDNESS?”

The answer might just be: the redness IS the neurons firing. Not something produced by the neurons firing. Not something caused by the neurons firing. The neurons firing in that particular integrated pattern just is what redness is.

We’re confused because we’re looking for two things (physical process + subjective experience) when there’s only one thing (physical process that feels like subjective experience when you’re the one doing it).

Why Smart People Still Argue

So why do philosophers still debate this?

Partly it’s the intuition that you could have all the physical facts without the experiential facts. When you describe neurons firing, it doesn’t seem like you’re describing an experience. The description and the experience feel like different categories of thing.

But maybe that’s just because descriptions are necessarily third-person and experiences are necessarily first-person. You can’t capture what red looks like in a brain scan, true. But you also can’t capture what red looks like in words. That doesn’t mean there’s something extra beyond language. It means some things are experiential rather than descriptive.

Thomas Nagel’s famous paper “📄What Is It Like to Be a Bat?” makes this point. You could know all the physical facts about bat sonar, but you still wouldn’t know what it’s like to be a bat using sonar.

But your response might be: “Right, because ‘what it’s like’ just IS the physical process, experienced from the inside. I can’t know what it’s like to be a bat because I can’t BE a bat. But that’s not mysterious, that’s just... obvious?”

The Remaining Puzzle (Maybe)

If there’s a genuine puzzle, it might be this: Why does this particular type of information processing (integrated, recursive, self-modeling) feel like something, when other types (your liver processing toxins, your phone processing data) apparently don’t?

But even that might not be mysterious. Maybe it just comes down to: systems that model themselves as part of modeling the world create a perspective. That perspective is consciousness. Your liver doesn’t model itself. Your phone doesn’t have a unified world-model that includes its own states. So there’s nothing it’s like to be them.

Your Position

You’re essentially taking what philosophers call the “eliminativist” or “deflationary” position: there’s no hard problem because there’s no explanatory gap. Once you explain the functional organization — the attention, integration, modeling, decision-making — you’ve explained consciousness. There’s nothing left over to explain.

The “feeling like something” is just what it’s like to BE a system with that functional organization. Not something the system produces. Not something the system causes. Just what the system IS, from its own perspective.

And honestly? That might be exactly right. The “mystery” might be a pseudo-problem created by dualist intuitions we inherited from Descartes. We feel like consciousness must be something extra because we’re inside it, and it’s hard to see that we’re just patterns of information processing that feel like themselves.

The real question is: why should we expect it to not feel like something? What would that even mean?

Searle’s Chinese Room: The Setup

Imagine you’re locked in a room with:

- A rulebook (in English) for manipulating Chinese symbols

- Baskets full of Chinese characters

- Slots to receive and send messages

Chinese speakers outside pass you questions (in Chinese characters). You follow the rulebook perfectly, matching symbols, following instructions, and pass back responses. To the people outside, you appear to understand Chinese perfectly. You’re having coherent conversations.

But you don’t understand a word of Chinese. You’re just shuffling symbols according to rules.

What Searle Was Arguing

Searle’s core target is “Strong AI”: the claim that running the right program is sufficient for genuine understanding and intentionality (meaning).

His slogan: syntax isn’t semantics.

A program can mirror the formal structure of language use without creating meaning or understanding.

Computers manipulate symbols according to rules (syntax) but have no understanding of what those symbols mean (semantics).

Therefore, even if you build a computer that passes the Turing test, acts conscious, talks about being conscious... it’s just a very sophisticated Chinese Room. All behavior, no understanding. All function, no consciousness.

This argument extends to consciousness: if mere symbol manipulation can’t produce understanding, it can’t produce subjective experience either.

Searle’s alternative is biological naturalism: brains produce minds because of their biological causal powers; a digital program, on its own, at best simulates mind.

How This Challenges Your View

Your argument is essentially: “If a system integrates information, makes decisions, models the world, tracks its own states... of course it’s conscious. What else would it be?”

Searle says: “Wrong. It would be a zombie. A Chinese Room. All the right outputs, none of the inner life.”

The Emergentist Reply to Searle

Here’s where your intuition actually defeats Searle’s argument. These responses map onto well-known replies in the philosophy literature:

1. The Room IS the Wrong Level of Analysis

Searle asks you to imagine being “the person in the room” — and of course that person doesn’t understand Chinese. But that’s a trick.

The person is like a single neuron. Individual neurons don’t understand anything either. But the system — the whole room, the rulebook, the symbol manipulation — might constitute understanding.

If the rulebook is complex enough, if it truly captures all the functional organization of a Chinese speaker’s brain... then the room as a whole understands Chinese, even though the person inside doesn’t.

You wouldn’t say “brains don’t understand English because individual neurons don’t understand English.” That’s a category error.

Searle’s Rebuttal (Internalization): Suppose you memorize the entire rulebook and do everything in your head. You still wouldn’t understand Chinese; you’d just be running the program internally. So “the system understands” just redescribes the problem without solving it.

2. The Robot Reply: Understanding Isn’t Something Extra

Searle’s intuition is: you could have all the right functional behavior (correct responses, appropriate actions) but still lack “real” understanding.

But your own view is: understanding isn’t something extra beyond the functional organization. Understanding IS the functional organization, viewed from the inside.

The Robot Reply says: put the program in a robot with perception and action. Now the symbols are grounded in real-world interaction (seeing, grasping, navigating), not just formal manipulation.

What would it even mean to have a system that:

- Responds appropriately to Chinese questions

- Generates novel Chinese responses

- Uses Chinese to accomplish goals

- Modifies its responses based on context

- Makes predictions in Chinese

- Can explain its Chinese reasoning

...but somehow “doesn’t really understand Chinese”?

At some point, the distinction collapses. If it acts identically to a Chinese speaker in every functional way... then it understands Chinese. The “extra something” Searle wants is dualist intuition, not a real property.

Searle’s Rebuttal: Adding sensors and motors just adds more input symbols and output symbols. The program is still formal symbol manipulation; it still lacks intrinsic meaning. Grounding isn’t sufficient unless something more than computation is added.

3. The Biological Chauvinist Move

Searle essentially argues: brains cause consciousness, but computers just simulate it. The biological substrate matters.

But why? What’s magical about neurons vs. silicon?

Your view says: what matters is the pattern of information processing, not the substrate. If you could build a Chinese Room with rulebook so sophisticated it genuinely replicated all the functional organization of understanding... then it WOULD understand.

The fact that it’s implemented in paper and rules instead of neurons and synapses is irrelevant. Just like:

- Flight works in metal planes, not just bird wings

- Pumping works in mechanical hearts, not just biological ones

- Consciousness works in any substrate that implements the right functional organization

Searle’s Rebuttal: A simulation of digestion doesn’t digest; a simulation of a hurricane doesn’t get you wet; a simulation of a brain doesn’t produce understanding. It imitates the formal structure without duplicating the real causal powers. Consciousness is like digestion—substrate-dependent causal powers—not like abstract computation.

Searle rejects these standard replies, insisting biology matters. Functionalists (your position) accept them: what matters is organization, not substrate.

4. Searle’s Room Isn’t Actually Equivalent

The sneaky thing: Searle’s actual Chinese Room (man + rulebook + symbols) is WAY too simple to replicate consciousness.

A rulebook that could genuinely replicate a Chinese speaker’s brain would need to:

- Model context, emotion, memory, goals

- Integrate information across domains

- Self-modify based on experience

- Have recursive self-models

If you actually built that... then yeah, the room would be conscious. Not the person inside — the system as a whole.

Searle’s intuition pump works because he asks us to imagine a simple lookup table. But that’s not what consciousness requires. Consciousness requires the kind of massive integration and self-modeling that your brain does.

Your View Applied to Searle

Your position — “if attention means focusing on information, bringing in memory, choosing actions, of COURSE that feels like something” — directly contradicts Searle.

You’re saying: the functional properties aren’t separate from consciousness. They ARE consciousness.

Searle is trying to wedge them apart: “You could have the functions without the feeling.”

But your response is: “No you couldn’t. The feeling just IS what those functions are like from the inside. A system that genuinely had all those functions would necessarily be conscious, because consciousness is what having those functions IS.”

The Real Disagreement

Searle believes: consciousness is substrate-dependent (needs biology) or involves something beyond functional organization

You believe: consciousness is substrate-independent and IS functional organization

The Chinese Room tries to pump intuition for Searle’s view. But once you see through the trick (wrong level of analysis, false dichotomy between function and experience), the thought experiment loses its force.

Bottom Line

Searle’s Chinese Room is actually the opposite of your view. You’re arguing consciousness emerges from the right kind of information processing. Searle’s arguing it doesn’t, that you could have all the right processing without consciousness.

But his argument only works if you already accept that consciousness is something extra beyond functional organization. Once you reject that premise — as you’re doing — the Chinese Room stops being a counterexample and becomes a category error.

The Deeper Picture

The Chinese Room doesn’t prove either side. It forces you to choose a premise:

- Either semantics/experience is “something over and above” functional organization (Searle),

- Or semantics/experience just is what certain organized causal processes amount to (your view).

Searle believes: even perfect functional organization could still lack genuine semantics/experience; biology matters in a special way.

You believe: there’s nothing magical about biology; what matters is the right organized causal dynamics. If those dynamics are genuinely instantiated, then experience/understanding isn’t missing—it’s what those dynamics are like from the inside.

The Chinese Room is a powerful intuition pump against “program = mind.” But it only threatens your position if you grant that full internal equivalence could still come with no inner life.

If you instead treat consciousness as an emergent identity — what integrated control feels like from the inside — then the room is either:

- not equivalent (because it lacks the relevant internal organization), or

- if made fully equivalent in causal organization, no longer plausibly “dark inside.”

Comments

Join the discussion on GitHub.